While the spectre of permanent loss of significant parts of territory looms over Ukraine - Slovakia`s eastern neighbour – Slovaks look the other way, some even support the aggressor and cheer the „separatists.“ Slovak social media landscape is flooded with pro-Kremlin narratives and content, often disseminated and multiplied by domestic actors, including fringe media, influencers and politicians. The infamous Russian Night Wolves bikers club have set up their European Headquarters in Slovakia and paramilitary groups indoctrinate young people with pro-Russian narratives. Our recent research on domestic and regional revisionist narratives tell the story of how a small country of 5 million, which has existed as an independent state less than 30 years, and it is so open to the Kremlin’s toxic narratives and vulnerable to its sharp power.

Slovakia is and always has been due to its history, small size and geographic position, very sensitive to any notion of territorial revisionism. Trianon Treaty, ending World War I, is seen as a cornerstone of modern-day Slovakia. The fear of territorial revisionism by Slovakia`s southern neighbour - Hungary - and irredentism by Hungarian national minority living in southern Slovakia has been a dominant factor driving the support for nationalist sentiments and political parties since the formation of independent Slovakia. While the peaceful breakup of Czecho-Slovakia in 1992 has been widely celebrated as a role model of a democratic political transition, the bloody ethnic wars and ethnic cleansing of the 90`s in the Balkans served as a constant reminder how easy nationalism bound territorial politics could spiral out of control.

Slovakia has never in its recent history expressed any territorial demands nor did it mourn any loss of territory since the formation of Czecho-Slovakia in 1918. Therefore, it comes as a surprise that according to the Pew Research Center survey, 46% of Slovaks consider that part of neighbouring country should belong to Slovakia. In fact, Czecho-Slovakia lost after WWII almost one fourth of its territory, the so called Transcarpathian Ukraine, to Soviet Union. Yet, the territory, which was part of Czecho-Slovakia only for some 20 years, has not been a topic of any real discussion about its return to modern Slovakia. If such attitudes indeed exist, as the research suggests, they are not manifested in the public nor in the political discussion. The notion of „greater Slovakia“ is non-existent in the media nor in the political discourse.

Moreover, there is an almost complete national/political consensus supporting the post-World War II borders of Slovakia. Therefore, any attempts to question or even change the existing borders in Europe, whether in the Balkans or elsewhere, are perceived as a potential threat to the territorial integrity of Slovakia. Such a perception is clearly visible also in the official Slovak position regarding the status of Kosovo and Crimea. Slovakia is one of the few EU member states which still has not recognised Kosovo.

Due to the almost universal national consensus rejecting any notion of territorial revisionism, which includes also fringe actors, there are no significant figures or entities actively promoting territorial revisionism. The only exceptions to this are the positions of fringe media, nationalist and fringe political parties and some paramilitary groups regarding the Russian annexation of Crimea. This case is however framed not as a revision of borders, but as a return to a “natural state,” which was violated during Soviet times by Khrushchev, who donated Crimea (which was allegedly always Russian anyway) to Ukraine.

These claims are reinforced by the positive attitude of Slovaks to Russia is, according to a recent Pew Research study, second highest in the world, with 60% viewing Russia positively and only Bulgaria having a higher score. Therefore, Slovakia is particularly vulnerable to information operations aimed at presenting Russia as a victim of Western aggression and its activities in Crimea and eastern Ukraine as fully legitimate, despite evidence to the contrary. Russian soft power in Slovakia is, therefore, quite significant and includes an eco-system of various pro-Kremlin media outlets: electronic, print, online fringe networks of media, politicians, extremist organisations and influential individuals, cultural and sport events and educational activities.

Despite strong pro-Russian sentiments, more Slovaks, at least initially, rejected the annexation of Crimea (38%) than supported it (35%). These attitudes however seem to be changing, also due to constant bombardment of pro-Russian narratives. The existence of such effective fringe media ecosystem coupled with significant affinity towards Russia and a lukewarm and hesitant pro-Western orientation among the population with large pockets of the population feeling nostalgia for the communist past create a fertile ground for active measures by Russian and pro/Russian actors.

Analysis carried out within our project confirmed that the coverage of events in Ukraine, including annexation of Crimea is very different in the mainstream and the fringe media, in effect creating two opposite versions of reality for their viewers. Fringe media cover any issues related to Russia, including the conflict in Ukraine, much more frequently, and they closely follow the narrative and perspective of Kremlin, either directly using text from Russian sources or using their talking points and reasoning. There is also growing mutual support and recognition between some fringe media and fringe politicians. Fringe media further disseminate their Facebook posts and provide them with ample space to reach beyond their traditional bubble, while politicians often use in their posts narratives widely disseminated by these media outlets.

Mainstream media, on the other hand, follow the official foreign policy of Slovakia – supporting the territorial integrity of Ukraine, the non-recognition of the Crimea referendum and Russian annexation. While fringe media manage to have viral content regarding specific incidents or events, in terms of overall volume, the bulk of the content is on mainstream media. However, fringe media manage to drive much more interaction and engagement on social media; therefore, their content often outperforms mainstream media.

Based on our analysis of representative samples of Slovak website articles, we found that fringe media narratives concerning Russia and Ukraine are connected by a single thread – the positive depiction of Russia and it actions in Ukraine and elsewhere, and the demonisation of the West (EU, NATO, United States) and its policies towards Russia (sanctions regime, Crimea). By repeating the same story of the Crimea referendum being free and fair, the Kremlin and its local proxies try to win the hearts and minds and change the still dominant narrative of Russian “little green men” illegally seizing Crimea from Ukraine. In their view, the sanctions regime is hurting Russia and Crimea; therefore it is the immediate short term strategic goal of Russia to create fissures in the unanimous support for sanctions at the level of the EU, including in Slovakia. The two main revisionist messages aimed at Ukraine’s destabilization either claimed that Crimea has been always Russian or Zakarpattia would be given autonomy or allowed to join Hungary.

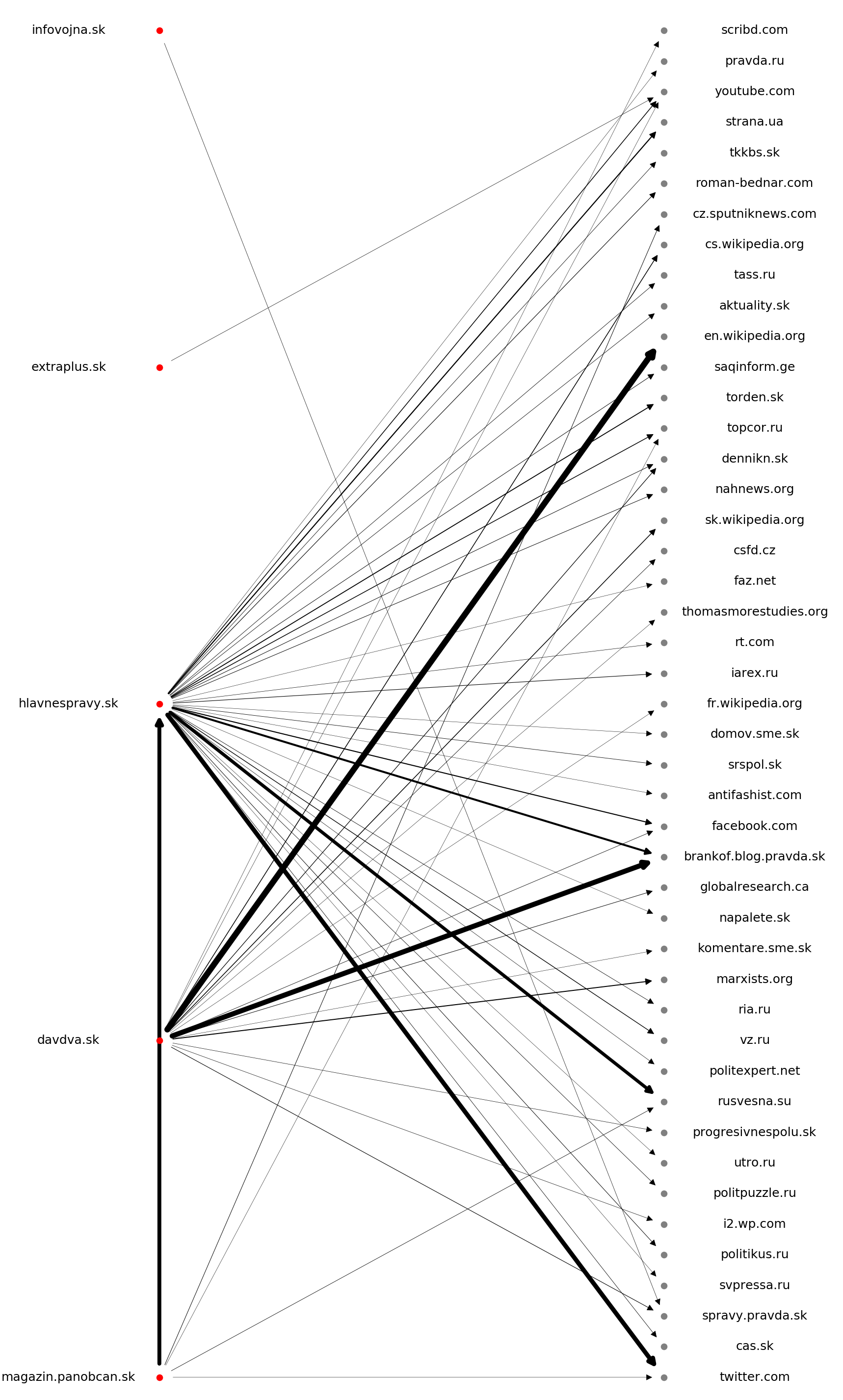

The hyperlink network of fringe pro-Kremlin websites disseminating revisionist messages in Slovakia

Our analysis revealed that the modus operandi of pro-Kremlin websites differs quite significantly in each case, based on the network analysis of hyperlinks connecting fringe websites and third-parties an– as seen on the graph below. While some outlets such as Hlavne Správy are heavily reliant on original Russian news sources, both official and fringe to legitimise their revisionism-related articles, others prefer to publish their own content without open or obvious links to Russian media. Increasingly such sources are trying to present themselves as the only truly independent media, which provide balanced, accurate and independent coverage of world events. Uncovering their many connections to Russian sources and pro-Russian narratives is therefore quite important in blowing this cover of alleged independence.

The two main portals proved to be far-right Hlavné správy using a significant amount of Russian language sources of de-facto authorities in Donbass and various Russian media and the leftist Dav Dva. The two reaching out to both rightist and leftist fringe audiences to the benefit of the Kremlin’s communication about “Fascist” Kyiv and a “freedom fight” in Eastern Ukraine.

Consequently, the Kremlin and its local allies are continually launching disinformation campaigns to antagonize EU or NATO member states based on current-day or historical revisionist ideas to legitimize the Kremlin’s geopolitics. The Trianon Treaty is used by pro-Russian Hungarian extremists and fringe media to incite hatred against Slovakia, Romania or Ukraine, while Slovak pro-Russian actors’ support of “separatists” drives a wedge between Ukraine and Slovakia. Therefore, these revisionist narratives, supported or disseminated by the Kremlin’s affiliates, present a direct national security threat for the Euro-Atlantic Community in general, and for the Central-European region in particular.

While each of the countries in this region is in a unique situation and has specific vulnerabilities, exposing the modus operandi and shedding more light on the actors and their connections to Kremlin could contribute to decreasing the overall impact and reach of Russian active measures.

Daniel Milo J.D.

This article is part of a series published about the research results of the project entitled “Revealing Russian disinformation networks and active measures fuelling secessionism and border revisionism in Central and Eastern Europe.” The research carried out in six countries – Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, Romania and Serbia – between 1 January 2018 and 15 April 2020 was made possible by the generous support of the Open Information Partnership.