The Romanian media space is considered one of the most resilient to Russian disinformation and communication campaigns. However, our recent study on territorial-revisionist narratives related to the outcomes of the Trianon Treaty pointed to the existence of certain vulnerabilities on both the Hungarian and Romanian side of the border that can be directly or indirectly speculated by Russia (and not just Russia) to further destabilise the region by utilising/amplifying revisionist claims.

Disinformation about Romanian-Hungarian relations as presented in Romanian mainstream and social media is primarily an illustration of home-grown mistrust between two communities lacking proper dialogue and knowledge of each other, a mistrust that, in addition, was historically cultivated as an instrument of manipulation during the decades of communism. External interference merely, therefore, amplifies domestic content and provides every now and then the additional spin that serves the interests of – most often – Russia.

Given the highly negative track-record of relations between Bucharest and Moscow, the population on the whole tends to be quite resilient in front of openly promoted pro-Russian narratives (interaction rates with Russian media outlets such as sputnik.md or Russia Today also remain low). However, Russian-backed local actors or ‘useful idiots’ whose agendas largely overlap with the Kremlin’s and who embrace similar rhetoric can be quite successful in their presentation of Romanian-Hungarian relations as irreconcilable. These also feed the Russian efforts to present Romania as a hypocrite, revisionist and interventionist state, aiming to reunite with the Republic of Moldova, and permanently interfering in Moldovan politics for that purpose – which is most often the focus of Russian propaganda. Only in isolated cases (such as a relatively recent interethnic incident in the Uz Valley over a war cemetery) are there signs of coordination between Russian outlets and the internal groups that are behind the flare in Romanian-Hungarian tensions.

Thus, the most frequent producers (and at the same time beneficiaries) of disinformation about Romanian-Hungarian relations are the (multiplying) far-right, nationalist, anti-liberal groups; political actors do jump on board when they identify an opportunity to harness interethnic tensions to collect votes, but generally refrain from translating inflammatory rhetoric into political action. Until recently, the theme mostly featured in the discourse of the more populistic Social-Democrats (absent any major far-right or otherwise radical political party in Romania, the PSD has tried to appeal to this particular electorate as well). Paradoxically, liberal and German ethnic president Klaus Iohannis tried to use the same language to recapture some of this audience not long ago, by playing on the requests for enhanced autonomy advanced by the Hungarian minority - but with mixed results, as he got a lot of negative fallout from some of his own core electorate.

In a representative sample of Romanian language articles in both mainstream and fringe media discussing the outcomes of Trianon Treaty and ethnicity issues associated with it (such as Romania’s anniversary of its 1918 Great Unification, i.e. the reintegration of territories once part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; the above-mentioned inter-ethnic incident in Uz Valley followed by a row of rather undiplomatic exchanges), less than half of the articles were in fact presenting revisionist ideas or positions against Hungary /the Hungarian minority in Romania. The general number of press articles containing unequivocal chauvinistic/ xenophobic assertions is rather low in Romanian media – which should not be mistaken, however, for the absence of such attitudes in the collective mindset.

The mutual social and cultural disconnect between the Romanian and Hungarian minorities are, on the one hand, the result of short-sighted government policies on both sides, which have generated socio-economic cleavages and inequality, and on the other side of occasionally deliberate attempts by both Bucharest and Budapest to maintain control over their respective communities in Transylvania and be able to use the rhetoric of autonomy when that served their interests. With the population in the rest of the country being rather ignorant of local realities in the counties with a sizeable Hungarian population, perceptions were largely formed by government or political communication and the media. This has led to historically-based stereotypes, shaped both in the past (by the socialist regime) and at the present time (by nationalists and populists), whereby a common Romanian identity and the feeling of national solidarity are largely shaped by the rallying call to unity against a plethora of external enemies that have forever coveted Romanian territories – Hungary among them, also through its alleged “internal agents”: Hungarian ethnics living in Romania. Calls for territorial autonomy from the Hungarian minority and the interference of Budapest-backed elements in stirring local tensions have provided the element of truth that has strengthened the credibility of such narratives.

Looking at the discourse around Romanian’s Centennial anniversary and that of the Treaty of Trianon (2018), one can easily note that most disinformation/ misinformation revolved around the nationalistic, ethno-centrist narratives exaggerating the unique role that the Romanian population have played in achieving the Great Unification and romanticising the events surrounding it. This amounts, as described, to the creation (or continuation) of an alternative national history meant to use rather widely-shared feelings of victimisation to generate commonality of identity and purpose. Such narratives identified in the course of the research are referring to claims about ‘the Great Unification (was) made by the Romanian people,’ ‘The help received during the process was not crucial or decisive’, ‘(the existence of) external, and internal occult forces acting to diminish/deny the importance of the 1918 Great Unification’, ‘reunification between Romania and the Republic of Moldova is of the greatest importance’, ‘Russia is aggressively promoting its policy of maintaining its sphere of influence/vassal states’, ‘there are important resentments among the European states (especially those who were on the losing side of the WWI) towards Romania’s Great Unification’.

These narratives are further facilitated by the rise of nationalism, nativism and the irresponsibility of political discourse, whose populist tones cater to these audiences. Such topics are picked up by mainstream media – including those that overestimate the role that Romania played in WWI and the Great Unification or calls for reunification with the Republic of Moldova. This kind of ‘border revisionism’ continues to be seen by a significant part of the population as acceptable and thus forces politicians to at least not oppose it openly (thus adding more fuel to the fire and feeding the Russian messaging about Romanian revisionism).

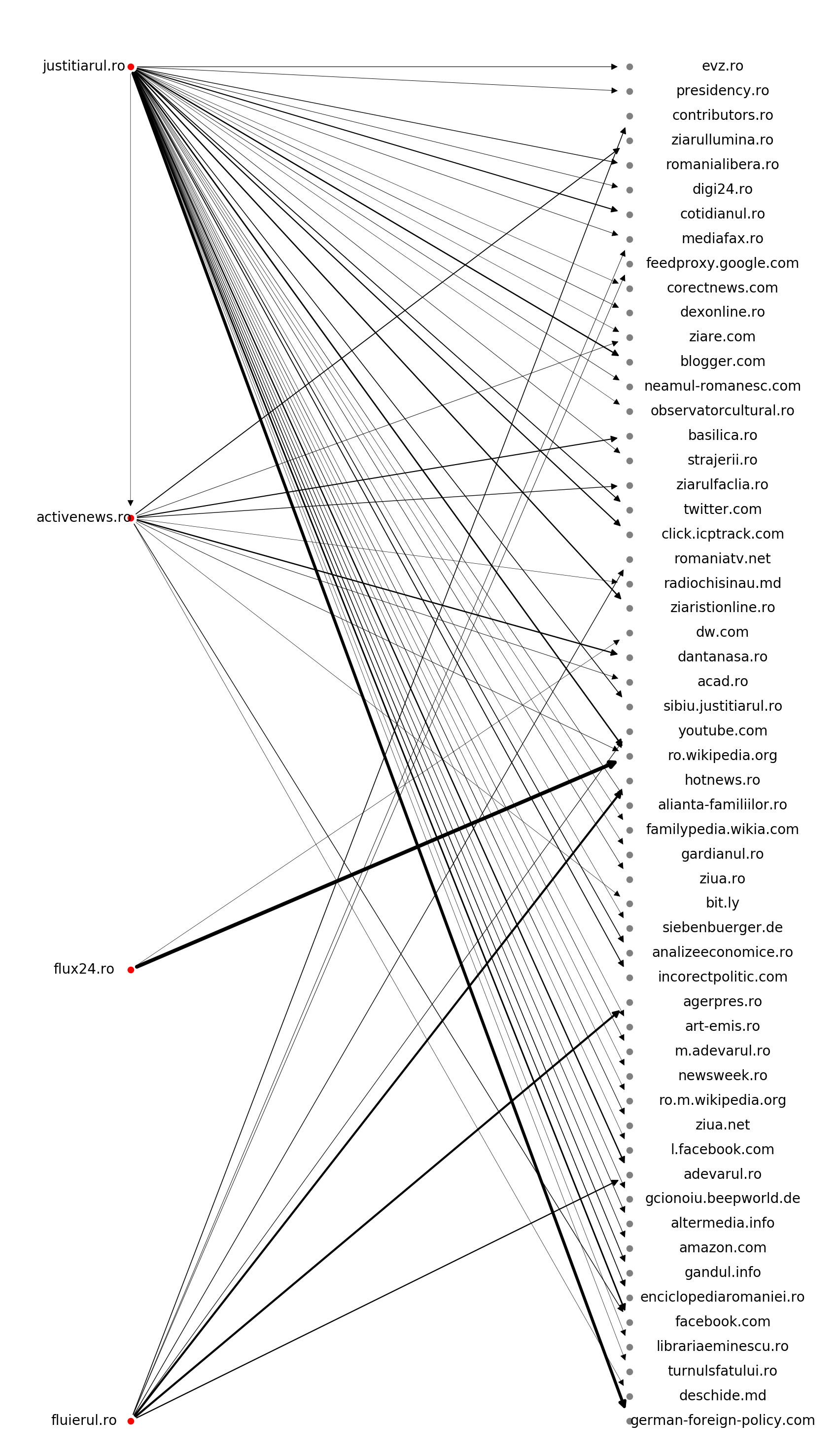

More fringe nationalist media will also distribute a set of narratives about Hungary’s alleged subversive behaviour, its “hidden agenda” in dividing Romania by supporting the secession of the Hungarian majority Szekler Land, and generally its actions as a regional disruptor. Among these, we could find narratives stating that ‘Hungary is supporting territorial revisionism in Szekler Land’, ‘Hungary has a hidden, historical plan to annex the territories it has lost as a consequence of the Trianon Treaty’, ‘Hungary is a vile state predisposed to mingling in Romania’s internal affairs’, ‘the ethnic Hungarian population in Transylvania (and their political representatives) are hostile to the Romanian population’, ‘Romania holds military superiority over Hungary’. These fringe media republish one another intensively and fuel an ecosystem gathering anti-liberal, orthodox groups together with far-right and xenophobic ones. The vocabulary used in promoting the narratives in this set is usually xenophobic and chauvinistic and is amplified by specific dissemination strategies. Fringe anti-Western, pro-Kremlin leaning media outlets employ a specific set of network strategies to amplify their reach and disseminate their narratives (oftentimes replicating Kremlin disinformation) by legitimising their content through hyperlinks to other trusted, mainstream sources or by cross-publishing contents of fellow fringe outlets – as seen on the graph of hyperlinks below. There are clearly strong bonds between the nationalistic, anti-Western media in Romania, and (to varying degrees) they support one another by republishing content or including hyperlinks to each other’s pages or Facebook page. Such websites are flux24, justitiarul.ro, and activenews.ro. One can easily observe that their common tactic is one of maximising their footprint by inserting hyper-linked references to as many other sites as possible by creating the impression that the information is clearly substantiated by other, legitimate sources (the mainstream digi24.ro, mediafax.ro, even presidency.ro). One example of such behaviour (the first outlet listed in the graph) is Justitiarul.ro, an electronic media outlet branding itself as fighting corruption and abuses, but in fact one of the most prolific disseminators of deep-state conspiracies and anti-establishment disinformation.

By comparing the presence on Facebook of Romanian five most effective far-right outlets and the five most effective conservative media, promoting narratives containing similar themes to Kremlin disinformation, the two most important characteristics of disseminated revisionist content were: ethnic prejudices or stereotypes about ethnicities; scepticism towards official interpretations of current-day or historical events. Finally, it’s worth mentioning the high number of followers shared by these fringe pages that also contribute to the successful dissemination or legitimisation of their narratives.

Altogether, our media analysis proved that Romanian “victimhood” narratives, together with the ones promoting “aggressive” revisionist ideas, pointed to a certain degree of vulnerability of the Romanian media space to both domestic and foreign-borne conspiratorial communication.

In a context where fringe social and online media increasingly influence mainstream media and radical political positions often push the agenda of centrist parties more to the extremes, a dialogue on thorny issues like Romanian – Hungarian relations can be difficult to initiate and sustain. As we presented in this article, these dialogue gaps are oftentimes instrumentalised by nationalistic fringe media that – knowingly or unknowingly – are promoting ideas that ultimately serve Kremlin’s hostile interests. Therefore, measures directed at reduction of inequalities among target populations (in our case, Romanian majority vs. Hungarian minority) are of paramount importance in helping bridge differences between ethnic or linguistic communities, while ensuring a healthy information space is also a key factor in the fight against disinformation. And as the problem is not located only at a political level (which rather opportunistically uses its pre-existence and helps perpetuate the situation), civil society organisations have an essential role to play in addressing these issues at grassroots level as well.

This article is part of a series published about the research results of the project entitled “Revealing Russian disinformation networks and active measures fuelling secessionism and border revisionism in Central and Eastern Europe.” The research carried out in six countries – Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Ukraine, Romania and Serbia – between 1 January 2018 and 15 April 2020 was made possible by the generous support of the Open Information Partnership. For more, please visit the project’s website here.