Jobbik’s voters were the most likely to be missing from the opposition coalition’s camp

Voters critical of the Orbán system are too diverse to be locked into a single camp. Our flash report suggests it was an illusion to suggest that the majority of former Jobbik voters can vote on a list with center-left parties. The maneuvering space of the fifth Orbán government will only be limited by economic and foreign policy necessities; domestically, it has an easier job than ever before.

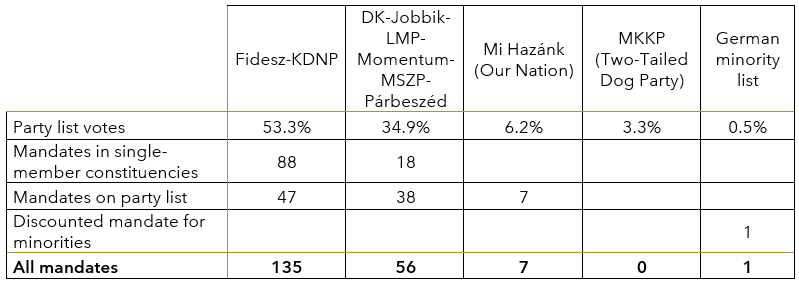

Fidesz won the 2022 general election with a larger vote share than ever before: they only gathered more than 50% of the vote in 2010 (52.7%), they gained 49.3% in 2018, while currently, they are on 53.3%, which could still increase to a slight extent after mail-in votes are counted. In 2014 and 2018, they got exactly two-thirds of mandates (133). In 2022, the party earned even more than that, at least 135, but this can also increase by one or two. The six-party opposition got 35% of the vote. When the six competed individually in 2018, they got 47% (together with Együtt, which is now defunct). The far-right, COVID-skeptic Mi Hazánk, which broke away from Jobbik after the 2018 general election, got into the National Assembly with 6% of the vote. The anti-establishment, former joke party MKKP failed to achieve this.

Results

The central force field is back. The opposition was expecting the closest election since 2006, but it got an even larger defeat than in 2010. In the next four years, Fidesz will have a larger constitutional majority than ever (their mandates could reach 137 after mail-in votes are counted), and Mi Hazánk made it into the Assembly. The latter party’s MPs are likely to mostly vote together with the ruling party. Therefore, the central force field was reconstructed, as there are parties both to the right and the left of Fidesz, and the actors on the two sides are incapable of cooperation.

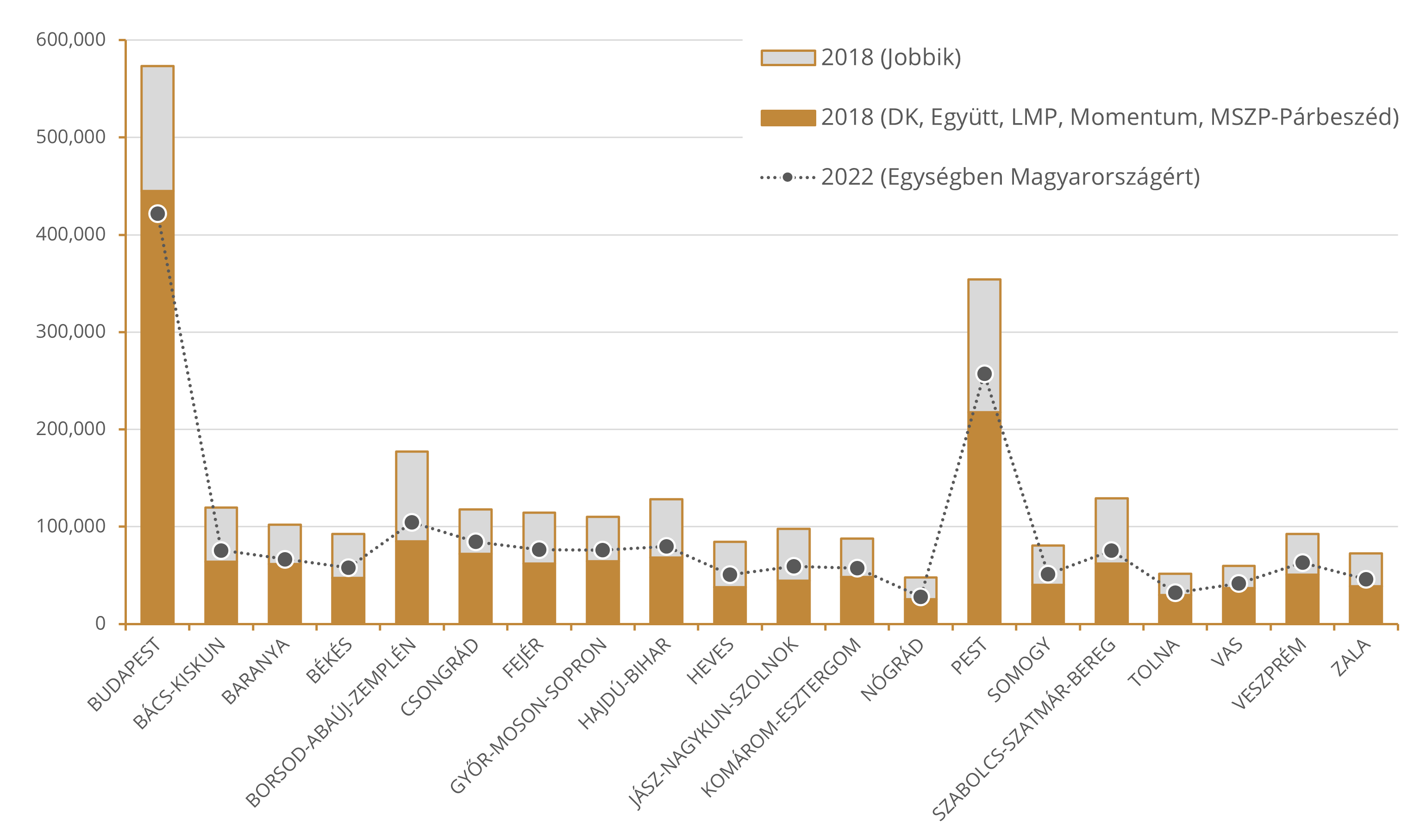

The “opposition voter” who was never born. The opposition cooperation materialized on the level of the six parties, but only some of the voters followed this strategy. In 2018, 1.6 million votes were cast on MSZP-Párbeszéd, DK, LMP, Momentum and Együtt lists and 1.1 voters chose Jobbik (within Hungarian borders). In contrast, the six-party list in 2022 only collected 1.8 million voters (after 98.96% of votes were counted). It seems that it was an illusion to suppose that the majority of Jobbik’s 2018 electorate would be willing to support the opposition cooperation. The majority of them could have ended up voting for Fidesz or Mi Hazánk.

We checked the number of party list votes cast on the parties of the cooperating opposition four years ago and today in the 19 counties and Budapest. The chart below indicates that in most counties, it was exactly Jobbik voters who were missing from the opposition’s camp:

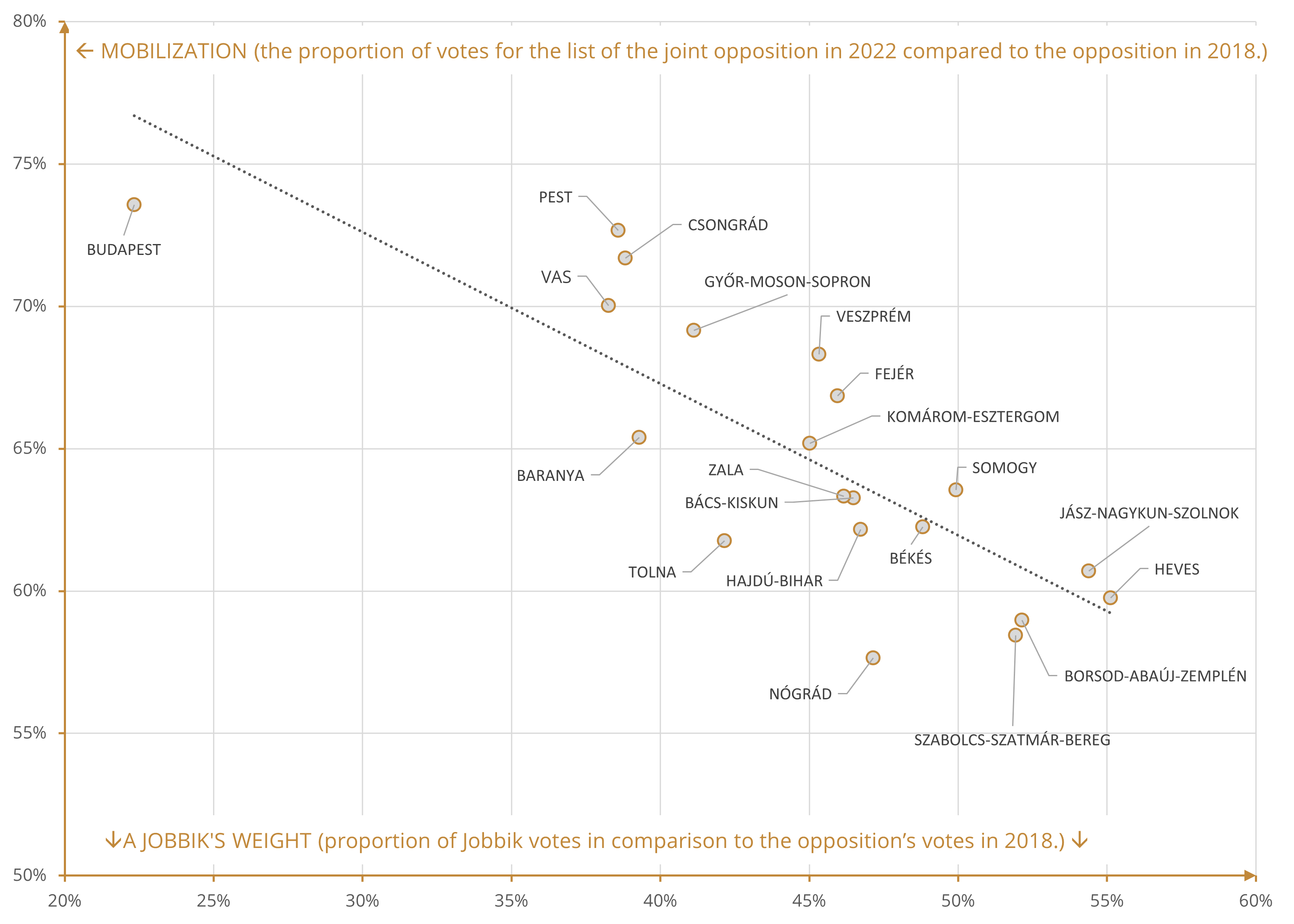

This would not have been ample evidence in itself, so we checked the weight of Jobbik voters within the opposition camp in 2018 (and that of other parties) in individual counties. The chart below shows that as Jobbik’s weight in 2018 increases, the opposition’s 2022 mobilization efforts deteriorate (the correlation between the two values is -0.81). Therefore, mobilization efforts failed the most in counties where Jobbik voters’ proportion within the opposition was high in 2018 (in contrast, in case of the other three larger parties, the counties where MSZP-P, DK and LMP were stronger, mobilization was more successful this year).

Since voter turnout was nearly identical, these values can be compared well even if Hungary’s population fell in the past four years. Center-left parties are likely only able to count on the support of the same 1.5 million voters, they are barely capable of gaining any new supporters.

After the primaries, the opposition did really replace itself. The campaign was paralyzed by the fact that parties did not accept the joint opposition PM candidate, and he himself stepped up as a rival to parties when he immediately demanded a seventh parliamentary group after the election. This quickly made everyone forget the success of the primaries and the results indicate that this even confused opposition voters. The fact that the PM candidate chose an erroneous political strategy when he wanted to reach an electoral group that turned away from Fidesz instead of the opposition and undecided voters also contributed to this effect.

War, power advantage. The ruling party’s messages of “peace” and their organization were effective partly due to the economic crisis and the brutal media advantage they possess, now even on social media. The poorer someone is, the more likely they are to identify security with the 12 years of the Orbán regime, while only seeing the risk of uncertainty in the opposition – if they even know of their existence. However, it is still untrue that the ruling party mainly has voters from rural areas and lower social classes – it was not true in 2018 either –, as Fidesz has strong support in all social strata. This was strengthened by the unprecedented financial distribution efforts before the election.

The imbalanced electoral system and access to resources did not only overcompensate Fidesz but strongly punished the opposition and simple mistakes they made. We do not need to talk about smear campaigns against the opposition, simply about the fact that their communication errors, lack of coordination are easily exploited in the ruling party-dominated public space.

Expected outcomes

Due to the results, the government will see all of its decisions to be validated, it has no reason for correction. This is what PM Viktor Orbán’s victory speech suggested as well. Fidesz can be confident even though the party is facing its toughest electoral cycle, as this could only be a threat for Fidesz if there was an opposition alternative, which is unlikely to be built in the foreseeable future after such a large loss.

The most likely scenario is that the autocratic political system is extended even further. The conquest of the judiciary can be finished, which is the last, still partly free branch of government, the space for free discussions will be even more limited, and the regime can become even more authoritarian as a response to the deteriorating economic situation. Only external (EU-NATO) controls will remain on their power, which can be expected to become stronger as a result of the Russo-Ukrainian war.

The opposition will likely collapse completely. They have already started searching for who to blame, deflecting blame from themselves, but nobody can avoid facing the consequences of their actions in this case. Although the presidents of Jobbik and DK have immediately blamed Péter Márki-Zay, they did not mention their own responsibility and did not talk about how badly their own candidates performed compared to expectations.

Potential foreign policy effects

Viktor Orbán’s position in negotiations improved vis-á-vis the European Union, as Brussels might once again perceive that Fidesz has no alternatives in the country. The European Commission (EC) and the new government could agree on RRF subsidies in the foreseeable future. The EC would then have the conditionality mechanism as a weapon to try keeping the Hungarian ruling party within a few red lines.

The ruling party’s policies on Russia will not change. The government will not veto sanctions but they might block extending them, especially in case there was a proposal to restrict EU energy imports from Russia. It is not impossible, however, that they will spend some EU subsidies on restricting Hungarian dependence on Russian natural gas, but mainly with the aim of improving their negotiating position vis-á-vis Moscow.

Fidesz could become even friendlier to China. In the case of Beijing, they are not forced to clearly take a side – unlike in the case of Russia. We can expect even more joint projects with China. After their electoral loss, the opposition’s Fudan referendum could fail altogether, giving a green light to that construction.

From the elections to forming a government

- The final results of the general election – The first sitting of the new National Assembly will be set to within 30 days of election day by the president – no later than 3 May 2022.

- The first sitting of the National Assembly (the formation of the Assembly’s committees) – early May 2022 (possibly even before the final results)

- Election of the prime minister – early May 2022

- Formation of the new government – mid-May 2022

- First sitting after the new government is in place – early June 2022

- Last sitting before the summer break – early to mid-July

- Start of the autumn session of the Assembly – mid-September 2022

The schedule above is party regulated by written laws, partly by customary law.