The Belt and Road Initiative: Visegrad Four’s Chinese dilemma

China has used the international economic crisis to elbow its way towards a dominant position on the global market. Its New Silk Road is seen as an attempt to create a massive, multi-national zone of economic and political influence, including in Central Europe. EURACTIV Poland/Czech Republic/Slovakia and Political Capital report.

In that context, it is logical that the Central European region should be an important part of Beijing’s Go Global outlook, as it is seen as a “side door” to the richer Western European markets. But Beijing’s flagship initiative has so far failed to attract significant attention in the Visegrad countries, though analysts believe its appeal may grow.

In 2012, China launched the so-called 16+1 framework – a platform for China-CEE cooperation – as a final landmark decision of the outgoing PRC premier Wen Jiabao. It comprises 16 Eastern European countries including all four Visegrad states (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia) and 11 EU member states altogether.

Since the current president Xi Jinping announced in 2013 the flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as the New Silk Road), 16+1 has focused mainly on infrastructure to match this cooperation with Beijing’s general global strategy.

But the Visegrad group is also trying to work out the well-known “Chinese dilemma”: Is the opening up to the Chinese presence in the region a unique economic opportunity or a threat?

An umbrella for Chinese activities

The underlying goal of the BRI, with 16+1 as one of its elements, has been to “re-orient the entire economy of Afro-Eurasia toward China as its centre. But the hard economic statistics show that there’s not much in BRI for V4 to get excited about,” according to Salvatore Babones, a professor at the University of Sydney. China is still poorer than all four Visegrad countries, and its modest spending on BRI is diluted among dozens of partners hungry for investment.

Ivana Karásková, a research fellow at Association for International Affairs (AMO), a Prague-based think tank, said the initiative’s main aim is to export Chinese overproduction overseas.

“The New Silk Road is just an umbrella for Chinese activities in Europe, Asia and Africa and does not have any concrete features,” Karásková told EURACTIV adding that it is hard for regional stakeholders to imagine anything particular under the BRI. AMO has launched a website, Chinfluence, dedicated to analysing the Chinese impact in the region.

Despite the quick and significant rise in Chinese foreign direct investments (FDIs) in the Visegrad countries, their volume also remains minor and focuses on mergers and acquisitions, lacking significant infrastructure projects.

In terms of infrastructure investment in the 11 EU members of the 16+1, “cooperation on infrastructure remains close to zero, despite intensive political contacts with China,” due to the incompatibility of the Chinese offer with the EU law (assuming state aid and the lack of open tenders), as Jakub Jakóbowski and Marcin Kaczmarski from the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW) explained.

The only exception is the flagship Belgrade-Budapest 336-kilometre rail line investment which ended with the EC’s probe into the Hungarian part of the project and with a final change of cooperation conditions on Budapest’s side.

Opportunity to diversify export markets

However, the Visegrad governments consider the BRI a major opportunity to strengthen trade flows from both sides. Currently, the relatively small V4 economies run a drastic deficit with China.

“If we are looking for ways to diversify our trade portfolio and reduce our dependency on the European market, this may be one of the solutions, although not the only one,” Czech MEP Jan Zahradil (ECR) told EURACTIV.

When the first trial train with containers from Dalian – the largest port in eastern China – arrived in Bratislava last year, the Slovak Government’s deputy for the Silk Road project, Dana Meager, described it as “one of the most important pillars of further development of the national economy”.

All V4 governments want to deepen mutual cooperation and attract more foreign direct investment to widen the array of financing and investment opportunities provided by the EU.

If the new EU multiannual financial framework reduces funding possibilities for V4 countries, be it as a result of Brexit and/or reshuffling of financial priorities, “then China’s offer could automatically become more attractive,” warned Jakub Jakóbowski and Marcin Kaczmarski from the Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW).

But Chinese foreign direct investment in V4 countries is not really growing and has, in fact, decreased in some of them.

“The old model of globalisation is over”

Czech MEP Jiří Pospíšil (EPP) thinks that the whole project is more of an instrument of Chinese propaganda and a reinforcement of Chinese influence.

“If one party is to benefit from the cooperation, it is China and Chinese companies,” he adds.

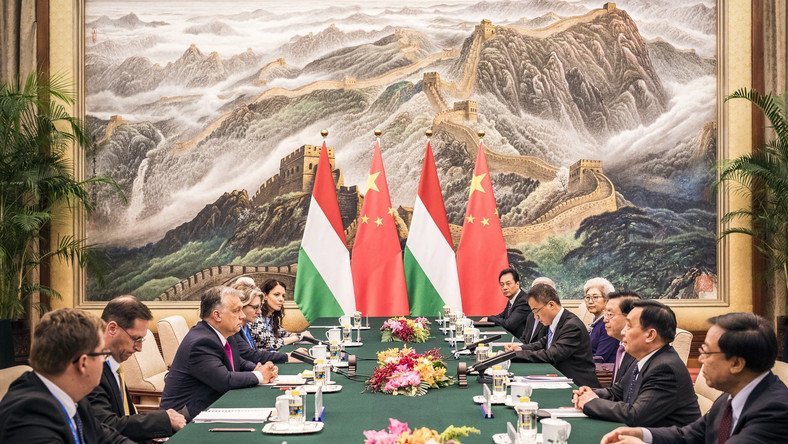

For example, when joining the BRI in 2015, Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán indicated that he is completely unmoved by the reigning political system in China. “The old model of globalisation is over, ‘the East has caught up to the West’, and a large part of the world has had enough of being schooled on, for instance, human rights and the market economy by developed nations,” he stressed.

Moreover, Beijing certainly values political gestures, such as when Hungary, together with Greece and Croatia, blocked a joint resolution on the South China Sea in 2016, as well as the fact that Hungary stopped the EU from signing a declaration standing up for lawyers and human rights activists being tortured in China.

Strengthening cooperation between China and European countries may also be a problem for the EU “because many EU members prevent the adoption of common position towards China, e. g. in the area of human rights, investments screening or a market economy status,” said Karásková.

But analysts also stressed that several other high-level politicians – with Czech president Zeman as the most striking example – as well as officials and the media help the Chinese government expand its power in Europe.

However, most analysts are convinced that political destabilisation in V4 countries is not in the Chinese interest and thus poses no threat to the unity of the European Union.

“I firmly believe that the main aim of China’s influencing efforts is Western Europe and not Central and Eastern Europe,” said Tamás Matura, an expert on China and a professor at Corvinus University in Budapest.

“There is no doubt that the 16+1 initiative will increase Chinese influence in CEE, but it also creates a win-win situation and brings new opportunities to develop the region,” the former Hungarian Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy told Political Capital.

By Adéla Denková, Edit Zgut, Karolina Zbytniewska, Lukáš Hendrych and Marián Koreň | EURACTIV.cz, EURACTIV.pl, EURACTIV.sk and Political Capital