The Rise of the Canadian Far-Right

It is often assumed that Canada, the pinnacle of multiculturalism, is immune to right-wing extremism. For years however, Canada has been home to over 100 far-right groups who rally behind the preservation of race and culture. Similar to other groups around the world, the Canadian far-right works in an environment focused on otherness and what is referred to as staunch nationalism. While it has traditionally encompassed anti-Semitism, anti-black, and anti-Indigenous rhetoric, the target in more recent years has been the Canadian Muslim community and an ever-strong anti-immigration narrative. This report is written by Farah Rasmi, student at Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto and intern at Political Capital.

Amidst waves of extremism that flooded the western world, be it in Europe or the United States of America, Canada’s own multiculturalist identity has come under scrutiny. Despite some claims that the Trump election was the reason behind the apparent rise in hate crimes, the far right has actually been active in Canada for decades, more specifically after the 2015 refugee and migrant crisis in Europe. Bloody images of the attacks in France and Germany, as well as other European countries increased the fear of radical Islam and what the so called Islamic State amongst can bring to Canada. That said, while the Trump election did not instigate the creation of far-right groups, it has definitely emboldened their activities throughout Canada, even serving as an example for some people. Accordingly, most of the country’s radical groups had been around before the Trump elections.

The Canadian far-right is present across the Canadian nation, from British Columbia to Québec. Some, but by no means all, of the most significant groups are: La Meute (The Wolf Pack), Atalante, Soldiers of Odin, Three Percenters, Pegida, ID Canada, Hammerskins, Jewish Defence League, Storm Alliance, and Northern Guard.

Photo from Jewish Defence League Canada Blog

A significant common denominator between these groups has been their anti-immigration and (very often) their anti-Islam stance. While some like La Meute have smoothed over their narrative over the last year claiming that their fight is against radical Islam and illegal immigration, others like Pegida are openly against Islam. Groups like Alt-Right of the United States, are less prominent in Canada despite their apparent start in Toronto, according to their leader Richard Spencer. On the other hand, many more groups are only active online, and their activities are limited to forums such as Stormfront, the international white supremacy platform. Canada is also home to several notorious alt-right or alt-light figures, including but not limited to: Lauren Southern, Gavin McInnes, and Stephan Molyneux.

Interestingly, very few of these groups are a solely Canadian creation, most of them are inspired or directly linked to other groups throughout the world. For instance, Soldiers of Odin is an offshoot of the Finnish Soldiers of Odin that was founded in 2015 by Mika Ranta, a white supremacist, after the start of the refugee and migrant crisis.

Soldiers of Odin in Vancouver, Canada. Global News Hour Video.

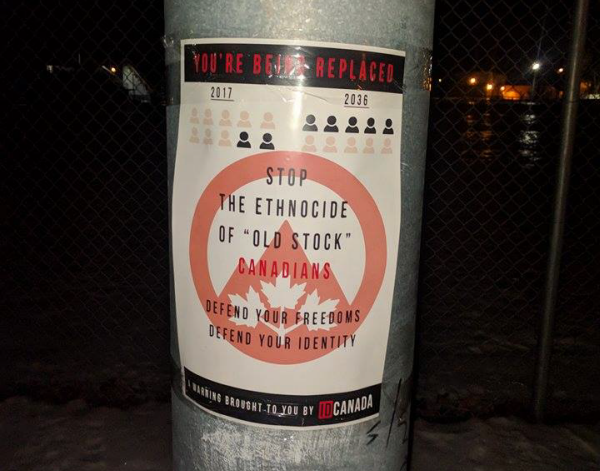

La Meute looks at France’s Marine Le Pen and her Front National for inspiration. In fact, in an interview with CBC News, La Meute's media liaison, Sylvain Maikan said "Marine Le Pen is a lot closer to us than Donald Trump." Pegida is also an offspring of the original German group created in 2014, to which it owes its name. Also, ID Canada, the Canadian branch of the pan-European Génération Identitaire that began in France. ID Canada has divisions all over the country, its proclaimed mission is “Homeland, Freedom, Tradition” and it has a direct affiliation to its European counterparts based on their belief that “Canada is not a “Nation of immigrants”. It is a nation formed by Europeans.”

Moreover, groups like Fédération des Québécois de Souches (FQS), founded in 2007 are identitarian neo-nationalist groups that proclaim the defence of the Québécois-European heritage and white supremacy. That is, they are also very similar to Génération Identitaire, although much older and relatively less active. On the other hand, Atalante, a group described by the Soldiers of Odin leader as too extreme even for them, is inspired by the Italian CasaPound in its activism. In fact, Stormfront an American-born forum that extensively serves to unite the Canadian far-right, also services multiple countries around Europe, including Hungary. As for the individuals, Gavin McInnes is a British-Canadian media personality based in New York who was also affiliated with Rebel Media in the past and is notorious for his right-wing leanings. Lauren Southern, a reporter previously affiliated with Rebel Media, has travelled to Europe on several occasions in order to meet with individuals from Génération Identitaire around the continent. She also joined them in their attempts to stop SOS Méditerranée vessels from saving refugees in the sea.

Lauren Southern in France with Génération Identitaire at La Traboule. Posted on Lauren Southern’s Twitter Account.

The activities of the abovementioned groups vary in scope and violence. La Meute, founded by two former soldiers who served in Afghanistan, proclaims over 40,000 followers online and about 5000 active members. It has chapters in various provinces and attempts to unite “like-minded” people in their fight against Radical Islam. This is done through protests, online groups and meetings.

Soldiers of Odin also have various chapters, but their most significant activity is organizing street patrols in what they deem dangerous areas, mostly areas with significant migrant populations who would be reminded of their existence and intimidated by their presence. ID Canada has opted for stunts similar to those of the Austrian and French Identitarians, putting signs in public spaces and claiming people’s attention. However, this activity is very recent and not much else has been done by the group that currently seems to be focusing on recruiting members.

Poster of ID Canada (ID Canada/Facebook)

FQS used to be seen as an activist group that was relatively visible in Québec, but it has recently focused on spreading its ideas through lectures and workshops whereas Atalante is said to have taken its place as the activists for the identitarian groups. Atalante’s entire premise is fighting for a neo-French Québec, in other words fighting anything that stands in their way.

Atalante Québec, [..], held a protest in October at the Citadelle in Quebec City. (Atalante Québec/Facebook)

The aforementioned groups do not necessarily fall into the divisions of Alt-right and Alt-light due to their ever-changing modus operandi and the changing ideologies. Some are clearly xenophobic and homophobic, some groups are exclusively male-centric and anti-women, some are against immigration, and other are against the liberal government as a whole. In interviews with Soldiers of Odin and La Meute there is a vocalized fear of Islam and immigrants taking over Canada and eradicating its culture. Often, Shariaa law is mentioned as a grave danger to the Canadian identity. On various forums, Facebook groups and media outlets the groups mention explicit fear of Islam and visible minority groups in Canada. On some forums anti-Semitism and anti-Indigenous sentiments are also vocalized. An increasing number of videos documenting incidences of hate speech or crimes have also been seen throughout Canada. For instance, a video from Alberta shows a man attacking and threatening a Canadian born man for his skin color. Another video shows a taxi driver being told to “go back to [his] country” while another one shows a woman’s outrage at some workers in a food court for their poor English skills echoing the same words as the man in the taxi and screaming “learn English.” The most violent and recent attacks, however, were in Québec City and Toronto. In the former, there was shooting in a Mosque which resulted in the death of 6 men and injured many more while they were praying in 2017. On April 23, 2018, Alek Minissian attacked pedestrians in a busy intersection in Toronto killing 10 people, the majority of which were women.

These attacks, while none were as violent as the one in Québec and most do not come close to what takes place in the US, have triggered much concern in Canada. Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and other Canadian security organizations have been discussing the extent of the threat over the last couple of years, with the most recent CSIS report describing it as a “growing concern” for the first time. Canadian laws on hate speech and hate crimes have also been a major reason for the control of right-wing extremism in Canada. Despite the far-right groups claiming free speech and the right of expression explicit in their campaigns, quoting the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Section 2), the Canadian Criminal Code (Sections 318-320) is intended to defend the citizen of potential abuses disguised under free speech. Many of those reported in the videos have been prosecuted, the Mosque attacker has recently pleaded guilty to murder charges, and Alek Minissian is being charged with 10 accounts of first degree murders and 13 of attempted murder. That said, there are many places in which the Canadian law could use some improvements that would allow easier conviction of hate speech.

Nonetheless, the laws alone are not enough to stop the significant rise in hate speech and radicalism in Canada. Justin Trudeau has also been the subject of attack by these groups, some even proclaiming that he should be tried for treason for his role in the refugee intake and his current political and economic policies. In response to the divisiveness, the current liberal government is currently taking steps to fund de-radicalization programs and anti-racism campaigns. Canadians are also very vocal about their intolerance for racist groups, which can be seen by the anti-racism protests that take place throughout Canada and almost every time a far-right right group protests. Most recently, at the Canada-US border, a far-right group tried to block a significant immigration route but was met with locals and anti-racism groups countering their rally.

Members of Peterborough Against Fascism march during a white supremacy demonstration on Saturday September 30, 2017 in Peterborough, Ont. CLIFFORD SKARSTEDT/POSTMEDIA NETWORK

Unlike in other countries of the West, far-right ideologies have largely failed to reach the government ranks. Despite individuals having slated alone in the past, no parties have run. Nevertheless, some of the aforementioned groups are now trying to get into the political scene as parties. So far, their attempts have been fruitless. Barbara Perry, an expert on right-wing extremism in Canada, explains this phenomenon by stating that the Canadian far-right had been very fragmented over the years, which contributes to its difference from its brethren in the south. The lack of organization and smaller audience have provided them with very little political advantage. Nonetheless, in British Columbia the Cultural Action Party, described by Perry as far right, have recently been given an official party status. Moreover, groups like La Meute, who openly denounce violence and claim rejecting racism, are hierarchal and extremely organized, they are also trying to widen their reach throughout Canada in a bold and often charismatic way that may someday lead them to politics. Lauren Southern, Gavin McInnes and Stefan Molyneux also enjoy a tremendous following and are generally able to rally people behind their ideologies that are often anti-feminism, xenophobic, anti-immigration, and LGBT+.

The Canadian far-right is thus definitely on the rise and it would be naïve to assume that Canada is immune to such trends. The nation has been home to neo-Nazis, KKK, and Skinheads for decades. The recently emboldened far-right is an echo of sentiments that are overtaking much of the world, and it provides a place for people with previously uncommunicated fears and a sense of racial superiority to unite. Canadian multiculturalism is thus not an antidote but a fertile field with much space for such narratives to be cultivated.