Fidesz most likely gained another two-thirds majority

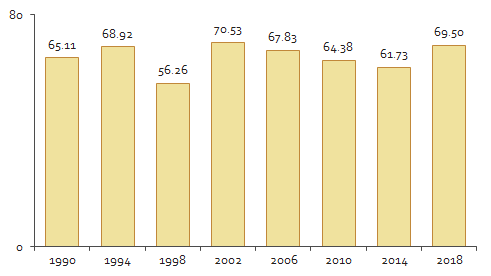

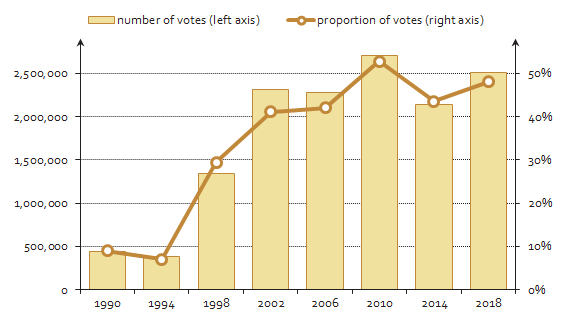

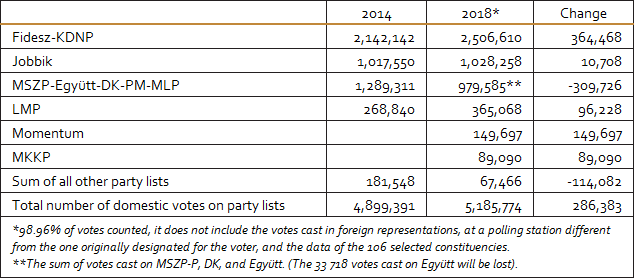

Election results will presumably grant the governing Fidesz another two-thirds majority in the National Assembly. The party gained a two-thirds majority with 48% of the votes this year (based on currently available data), compared to 52.7% of the party list votes in 2010, and 43.7% in 2014 (among votes cast within Hungarian borders)1. Hungary has become a successful laboratory of illiberal governance with an institutional system tailor-made to serve Fidesz’s purposes and goals, an unfair system; political rhetoric based on identity politics, conspiracy theories and enemy images, and a massive government-financed fake news industry. As the government received positive feedback from voters, a shift to a more moderate stance is unexpected. In terms of policies, no change is expected. There have not been too many concrete promises made by the governing party, although one exception is the promise of further tax cuts (personal income tax).

Only Fidesz gained strength in this election compared to its result in 2014, Jobbik largely kept its votes from 2014, while centre-left parties merely repartitioned the same amount of votes they had four years ago (in 2014, the MSZP-DK-Együtt-PM-MLP list and LMP received 1 558 151 votes altogether, while in 2018, the lists of MSZP-Párbeszéd, DK, Együtt, LMP, Momentum and MKKP received 1 538 440 votes on the ballots tallied so far). Moreover, the opposition lost 272 thousand of its 1,6 million votes (Momentum, Együtt, MKKP), which explains why Fidesz won exactly as many seats in the National Assembly as they did in 2014 despite the fact they lost 5 more single-member constituencies than four years ago.

The gap between results in the capital and in the countryside is enormous. 12 out of 14 mandates that the left-wing opposition could win were from Budapest. Only two left-wing candidates could win a single-member constituency outside of the capital (the socialist candidate was re-elected in Szeged, and independent candidate Tamás Mellár won a mandate in Pécs). In Budapest, left-wing candidates won a further 4 constituencies in addition to the 8 they won four years ago, not independently of the fact that comprehensive left-wing cooperation was agreed upon in numerous single-member constituencies in the capital. Jobbik’s failure is considerable compared to its own expectations, it managed to win only one mandate in single-member constituencies (Dunaújváros). Fidesz won all the rest of single-member constituencies: 91 of them. Jobbik’s leaders find themselves in a really tough spot as a result of the party’s electoral performance, their position within the party has been shaken. However, giving up on the “moderation” strategy is unlikely to benefit Jobbik considering the fact that Fidesz has largely conquered the far right of the political spectrum.

The governing party’s victory was basically secured by the following facts:

- Fidesz has had a unified voter base for a long time, while the opposition is fragmented. This is the “central power field,” which continues to work. Fidesz’s right-wing opposition is Jobbik, and the left is divided, consisting of numerous parties that are competing with each other. The Hungarian electoral system favours the strongest party, 106 out of the 199 seats in the National Assembly are decided in single-member constituencies; the opposition did not coordinate effectively, thus votes cast on the opposition were spread between numerous parties, meaning Fidesz could easily win mandates in single-member constituencies. Therefore, the opposition bears considerable responsibility for its own loss, as it failed to agree on effective cooperation in past years and build up candidates with a real chance to win. It was unable to benefit from the change of the public’s mood in the wake of the by-election in Hódmezővásárhely, while Fidesz learned from the defeat there and put considerable effort into mobilisation.

- Moreover, it is also important to note that the political environment built by Fidesz after 2010 did not provide the opposition with equal opportunities. The electoral system itself was not the central issue, it was rather the institutional system surrounding it. As the OSCE noted, the state and the governing party was inseparable in the election campaign. The State Audit Office punished only opposition parties during the campaign. The media environment in some regions of the country, especially in villages and small towns, created an informational ghetto where only the government’s campaign based on generating fears about migration could succeed. Corruption cases with ties to the government have not been investigated by the authorities, especially by the Office of the Prosecutor-General, properly.

Considering that Fidesz received positive feedback from voters, the style of governance is not going to change in the wake of the election result. The high voter turnout and the confident majority in the National Assembly provides the necessary legitimacy to the government to complete the political system it has built in the past eight years and to allow for even more repressive, authoritarian power politics. The government is going to further restrict the space for critical media and civil society organisations, and it will continue its “post-truth” governance with enemy images, conspiracy theories and fake news in the heart of its messaging.

1 The votes cast in Hungarian foreign representations and the ballots of those requesting to vote elsewhere than the polling station designated for them originally will be counted on April 14, which could alter the results in some single-member constituencies, albeit the likelihood of this is low. At the same time, only 70.000 of in-mail votes have been counted, so Fidesz’s two-thirds majority is rarely in doubt.