Knowledge about and attitudes on the Hungarian electoral system

“Not even those who count it understand it.” It is a frequent experience that many Hungarians have this attitude on the electoral system. If a system is impossible to comprehend, the electorate does not see the link between the ballot cast and the composition of the Parliament, which, in the end, undermines trust in the whole democratic system.

If there was a real reason why comprehensive electoral reform was justified already in 2010 (or even earlier), it would have been the system’s complicated nature. However, Fidesz and its two-thirds majority created a potentially even less transparent system. The only meaningful simplification was removing territorial lists from the equation (only the national party list and single-member constituencies remained), while the implementation of the Hungarian specialty called “winner compensation” made counting the fragment votes immensely hard to follow. Additionally, there is the suffrage of Hungarians living in neighbouring countries (hereafter referred to as ‘foreign Hungarians’); the fact they can only vote for a national party lists but in a completely different way than Hungarians living abroad but having a registered Hungarian address also does not make counting the votes easier. Moreover, the preferential nationality mandate also complicates the picture – and we are still talking about how votes translate into mandates without mentioning campaign rules, the chaotic way of fielding candidates and campaign financing.

This is exactly why we believe it was important to research how much the Hungarian electorate knows about parts and the whole of their electoral system and what their attitudes are on it.

Knowledge about the electoral system

Voters’ knowledge on the electoral system shows a mixed picture, especially considering the fact that Hungary was gearing up for its eight general election at the time data was being collected during the campaigning period for the 2018 general election. We formulated the questions to make our results comparable with Medián’s poll from 2009.

- 60% of voters knew that Hungarian voters receive two ballot papers. It can be considered a solid result compared to other findings, but it is lower than the 72% measured by Medián 9 years ago.

- Less than half of respondents (46%) could tell that a party needs to gain 5% of the vote on their national party list to meet the parliamentary threshold. This largely matches the data measured by Medián in 2009: then, exactly 50% knew what the parliamentary threshold was.

- In this light, it is especially surprising that the knowledge of one’s own single-member representative was considerably higher than 9 years ago: then, only every one in four respondents could correctly name their parliamentary representative. This time, two out five had the correct answer.

We can conclude that the elements of the electoral system that we consider the most commonly known are not evident to a considerable part of Hungarian society, and we can even see a declining trend in this regard. Hungarians’ awareness of who their parliamentary representative is has improved, but the number of respondents who answered this question correctly is still well below 50% (many respondents confused their parliamentary representative with the mayor). One could think that the improved awareness rate is the result of the name of single-member candidates being mentioned more frequently than ever in this campaign, but if this was the reason, knowledge about the number of ballot papers and the parliamentary threshold would have had to improve as well because these characteristics were also present in the public discourse in relation to initiatives encouraging voters to vote tactically.

Attitudes on the electoral system

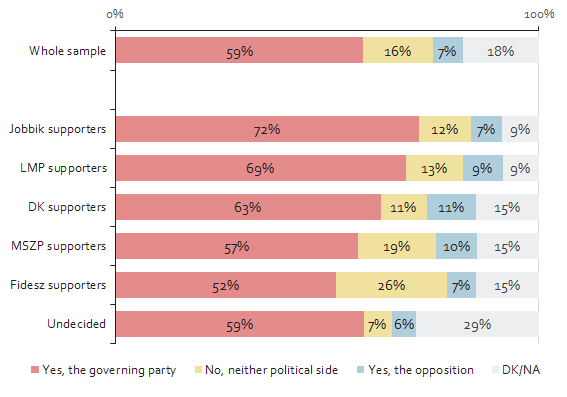

- The majority of respondents knows/feels that the electoral system approved in 2011 favours the largest party at the time of the election even more than the previous one had done. The opinion that the governing party is the beneficiary is even more prevalent: 59% believes this is the case, and only 7% says the opposition benefits from it. Only 16% thinks that the electoral system is unbiased, which is probably the most symptomatic data in the whole research.

- Even more than half of Fidesz voters think that the electoral system benefits the governing party – they are the least likely to think so with that result –, and only around one-fourth of them thought that the system was unbiased.

- Exactly half of all respondents said it was more important for Parliament to mirror the will of the voters proportionately than to ensure stable governance. The latter was preferred by 35% of respondents; Fidesz voters are unsurprisingly overrepresented among them.

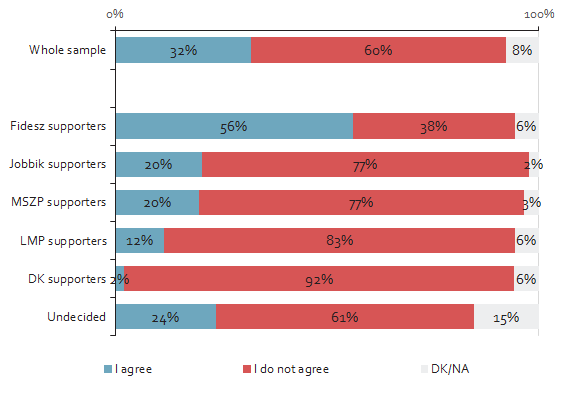

- The suffrage of foreign Hungarians, as earlier polls suggested, is still opposed by the majority (60%): it is unsurprising that DK voters were the most fervent opponents of it (92%), but 83% of LMP voters, 77-77% of MSZP and Jobbik supporters also disagreed with giving suffrage to foreign Hungarians, and pro-suffrage respondents were only in the majority among Fidesz voters.

- One result of the constant discourse about the electoral system could be that the majority of voters believe that the single-member constituency map drawn in 2011 also serves political interests, and they think the differentiation between how different groups of Hungarians living abroad vote is a serious problem together with the data protection issues that regularly come up in connection with fielding candidates.

The nation-wide, representative poll was conducted by Závecz Research on the commission of Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung’s office in Budapest and Political Capital. Data was collected between March 7 and March 14, 2018.

The complete study is available in Hungarian here.