Europe’s slow awakening – The societal and political results of the recent crises

It is not an exaggeration to say that we are living through years of crisis. The devastation of the coronavirus pandemic, the economic and energy crisis that has followed in its wake, and the escalation of the Russian-Ukrainian war that has exacerbated it, are posing a serious challenge to the current rules-based world order, and in many ways to Europe. Successful and unsuccessful disease control, unpopular pandemic restrictions, difficulties in making a living even in affluent countries, rising inflation, utility bills, the specter of recession and a sense of security undermined by Russian military aggression are testing European governments. In addition to the acute problems, there are also the constant challenge of global warming, and climate change, the significance of which was highlighted by the extreme drought experienced across Europe this summer.

This is a summary of Political Capital's study. The full paper is available here, in Hungarian. The project was supported by the Budapest Office of the Friedriech Ebert Striftung.

The current series of crises, however, are not without precedent. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 already exposed the vulnerabilities of the world economy. And the coronavirus outbreak has highlighted even more starkly the fragility of global supply chains. So it is no wonder that the current societal difficulties have reinvigorated the narratives within which many politicians and opinion formers, according to their perspectives and interests, predict the collapse of the Western-dominated world order, and as part of that, European governments and the European Union. Moreover, these interpretations of the current crises, combined with the social, cultural and political aspects of it, often project apocalyptic scenarios rooted in mis- or disinformation. These crisis narratives are particularly strong in Hungary - a NATO and EU member state - due to the dominance of the anti-Western governmental communication, and sometimes include statements that put even Putin's disinformation machine to shame in their visions of the West's demise.

In this paper, we will not go into all aspects of the impact of the crises. Instead, we will focus on three interrelated issues in the current situation: the challenges faced by governments, the perceptions of the European Union, and, as a consequence, the rise of the far-right in Europe. The fundamental question is how and whether European governments can successfully manage these problems? How do crises affect public sentiment? Can we talk about a breakthrough of the far-right or "fascist tendencies" in European politics? Does the Russian-Ukrainian war strengthen the role of the European Union and the need for further integration, or will the consequences of the war only divide the Union? These questions are all addressed in our analysis while stressing that what is written here concerns only the current situation, based on the events, facts and data that available at the moment. However, the trends examined cannot be directly extended into the future as all forecasts deal with a high level of uncertainty, given the constant changes in the situation concerning the energy and economic crises, and the outplay of the Russian-Ukrainian war.

While in the first year of the coronavirus, it seemed that the Eurosceptic voices might have been right, it now appears that European Union has been able to rise to the occasion and face head-on the challenges it faced based on unprecedented political, and economic unity. The question now is whether this unity can be maintained despite the deepening energy, and economic crises or the strengthening of political forces, such as populist or far-right actors, that are trying to tear Europe apart.

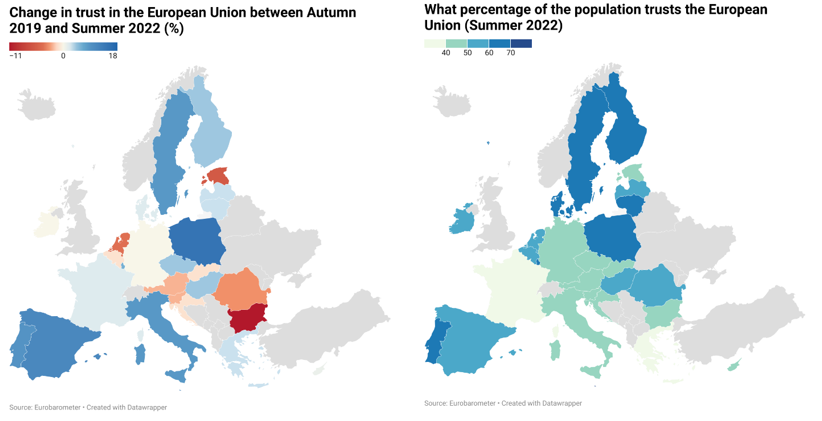

Overall, we can see that handling the crisis has increased confidence in both national governments and EU institutions. For national governments, the boost in confidence was temporary. According to the latest data from July 2022, 34% of Europeans trust their national government, while 49% trust the European Union as a whole as, compared to 34 % and 43 % three years ago. The trust in national government peaked at 40% after the first wave of COVID19 in the summer of 2020, while the trust in the EU peaked at 49% in February 2021 and reached 49% again in July 2022. Of course, the 27 countries present a varied picture regarding attitudes, however, but EU-wide figures show an increase in confidence compared to the year before the crisis.

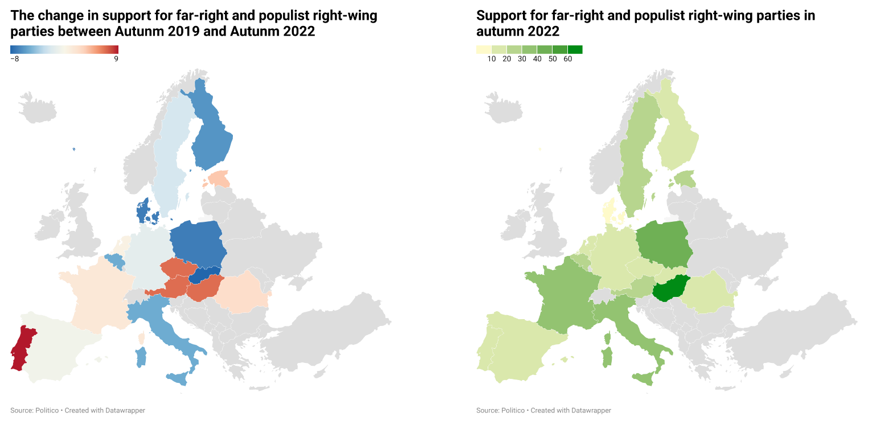

Contrary to previous concerns, far-right forces have so far failed to make inroads at the EU level over the past three years, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has reduced the appeal of pro-Russian far-right parties in many countries. Still, the crisis undoubtedly provides a fertile ground for the advancement of far-right and right-wing populist forces in the near future. So, while it is far-fetched to envision a 'fascist threat' on the European level, it is realistic to speak of a growing risk concerning individual member states – taking into consideration not so much the success of far-right parties in the Italian election but rather the examples of the Czech Republic and Austria, where the biggest far-right parties have seen their popularity grow. Portugal experienced an emergence of a populist right-wing party, but since it is around 7-10% popularity, it is still one of the smaller parties beside the two left-wing party.

Regarding European security situation, the European Union and NATO are also more united than ever due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Humanitarian, financial, and military aid provided to Ukraine, as well as the punitive measures were taken against Russia, all show that, contrary to expectations, the West has been able to act swiftly, unified and effective against an imminent threat. Furthermore, the accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO represents a major strategic defeat for Russia since the two Nordic countries would probably not have joined the military alliance without Russian aggression.

The West’s united pro-Ukraine stance, arms supplies, and sanctions have severely limited in the longer-term Russia's capabilities to wage war and have now plunged the country into recession. As a result, more than 1 000 international companies have left the country, and technological sanctions have crippled almost every sector of the Russian economy, from energy production to the military industry lasting for decades to come.

However, the energy crisis is caused partly by Russian retaliatory sanctions against the European Union, and by a general and global supply shortage of oil and natural gas production in the economic aftermath of the coronavirus. Russia's use of the so-called energy weapon was designed to bring Europe to its knees with low gas supplies in order to break the pro-Ukraine unity of the bloc and win the war. However, the radical increase in energy prices, especially gas prices, and the halt in Russian supplies are not expected to cause significant gas shortages in Europe, thanks to the replenishment of storage, energy saving measures and diversification of supply sources.

Despite the prevention of significant gas shortages in the EU, inflation and, in particular the rise of energy prices, will pose serious challenges for governments, at least in the short-term. Rising prices will particularly affect the lowest income groups in society, threatening to cause a social crisis if governments fail to support the most vulnerable, and prop up welfare measures. Consequently, social discontent rooted in economic hardship could reduce confidence in governments and even lead to demonstrations and protests in many major European cities – as predicted by many Eurosceptic or far-right political actors. The most important task in the coming months will be to support vulnerable groups at home and maintain financial and military aid provided to Ukraine.

While, contrary to pro-Kremlin propaganda, the West is not directly involved in the war, maintaining support for Ukraine is crucial for Europe and the West, as Ukraine is not only fighting for its national survival, but also for the security of Europe and the integrity of the current rules-based international order. The defeat of Ukraine would seriously undermine the security of the European continent, and the European countries must therefore do everything in their power to support Ukraine, as this is not only our moral duty, but also our security interest. After all, Russia poses a direct military threat to Ukraine, and the entire Western alliance security system. All this makes a Europe a kind of hinterland of the defensive war waged by Ukraine.