The elections swept away the established opposition, hit Fidesz, and touched the European mainstream, but the political system change has been cancelled both in Hungary and in Brussels

Domestically, the election results are unlikely to derail the Orbán regime in the short term, but a newcomer has entered the political arena who could be a serious challenger in the next parliamentary election. Although Fidesz’s results cannot be considered a grave failure by objective standards, they are underwhelming compared to the high goals set by Viktor Orbán, Fidesz’s hegemonic position and its agenda-setting power. What the various actors will do with the results of the double election in the coming weeks and months will be decisive. Those who expect the Orbán regime to loosen its grip on power will be disappointed. The following two years will be a period of slow agony for most of the losing opposition parties.

At the European level, there has been no breakthrough of the far right, but mainstream parties have weakened. The gradual shift to the right could cause leadership challenges in both Member States and the EU. As far-right parties are likely to remain fragmented due to ideological and political differences, their influence on decision-making remains limited, while Viktor Orbán seems to be swimming against the mainstream, even on the far right. However, the potential for authoritarian influence has increased slightly. A few weeks after stopping Brussels in the elections, Hungary will take over the EU Council presidency.

Domestic results: Despite its victory, the election was a failure for Fidesz

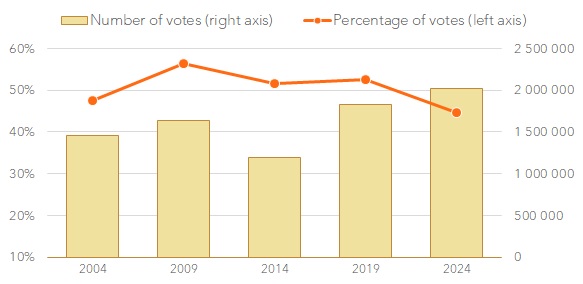

The number and percentage of votes cast for Fidesz-KDNP list in the EP elections (The 2024 data shows the results with 99.98% of the votes counted.)

Fidesz’s result cannot be considered a glorious victory, but at best a decent position. Fidesz performed worse in terms of vote shares than in any previous European Parliament election. However, this does not mean a total failure, as the party managed to cross the 2 million vote threshold, partly due to the 2 billion forints spent on online advertising since the beginning of the year. This result was still enough to win more than half of the 21 seats (11), mainly because about 11% of the votes were spread among parties that did not pass the threshold and therefore won no seats. The real sense of victory for Fidesz would have been the defeat of Budapest’s mayor, Gergely Karácsony, but this did not happen (although the outcome might still change due to a recount on 14 June). However, Fidesz managed to ensure that the composition of the Budapest City Council will be fragmented, making it difficult for the mayor to forge a majority.

The election results are not expected to shake the Orban regime, but the new challenger could pose a serious threat in the next parliamentary election. Péter Magyar – former ruling party insider-turned-rival – and his Respect and Freedom (TISZA) party scored 30%. In other words, for every 3 Fidesz votes, there are 2 TISZA votes. The high result could provide a good basis for the emergence of a strong and united opposition force against Fidesz by 2026. To be this force, TISZA must be able to absorb the remaining opposition voters and sway away more voters from the Fidesz camp than at present. For this, TISZA needs to build a real party organization with 106 strong candidates in the single-member constituencies. The grace period in which Péter Magyar can reach the masses online organically without advertising will soon be over. The 22 months until the 2026 general elections is only a seemingly long time.

The nature of the Orbán regime will not change. Fidesz will utilize all its power and means to discredit and undermine the emergence of Péter Magyar and his TISZA party. The ruling party does not see the reason for the unfavorable election result in the excessive concentration of power, repression or smear campaigns against the opposition, but on the contrary: the regime will further consolidate its grip on power. Not only will Fidesz seek to stifle the new challenger, but the free press and local governments can also expect their room for maneuver to be reduced. Especially since an economic upturn is still unlikely.

Remnants of the opposition outside the TISZA party are fighting a rearguard action. Although these established parties still have seats in the National Assembly, they might be better off focusing on the municipal positions they have won. However, even these positions hold little promise for the future. The fading opposition parties framed this year’s EP and municipal elections as a showdown among themselves to determine their relative position. However, the voters opted to vote for a party that was not fighting for second place but – at least in its messages – wanted to defeat the ruling party. Unlike the established opposition parties, TISZA showed strength and determination to succeed. The Democratic Coalition (DK) will aim to stay relevant. However, it had declared outright that the opposition needed a dominant party—having itself in mind—so it would be difficult to argue for its right to exist. While Momentum failed to win seats in the European Parliament and the Budapest Assembly, which poses an existential threat, the party has paradoxically achieved partial success in the countryside, with a total of 37 county assembly members. The other four parties involved in the six-party cooperation in 2022 will slowly erode until 2026 when their parliamentary group will cease to exist.

Our Homeland (Mi Hazánk) survived the elections. The far-right party also suffered significant losses due to the rapid rise of Péter Magyar. Half a year ago, Our Homeland was set to become a medium-sized party, but it did not even come close to it and was pushed out of the third-party position. Nevertheless, their county results (62 mandates in county assemblies) and the confident winning of a single seat in the EP prove that they have a solid organization. It remains to be seen with which allies, but they will strengthen the anti-EU, anti-NATO, anti-Western, pro-Russian, and authoritarian-friendly actors in the European Parliament.

Europe could see a gradual rightward shift and leadership crises instead of a far-right breakthrough

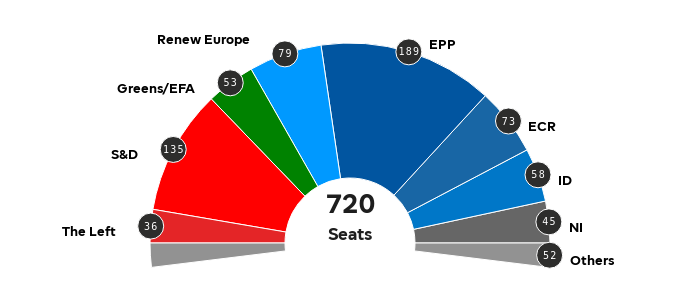

European Parliament 2024-2029 (provisional results; source: European Parliament)

The EU mainstream has weakened but not collapsed. Although Fidesz has made the change of European elites, European "regime change," and the occupation of "Brussels" the main goals of the European elections, in addition to avoiding and stopping war, the EU mainstream has not been shaken. In fact, Fidesz's old political family, the European People's Party (EPP), is the biggest winner of the European elections: they managed to increase their parliamentary group by 13 MEPs to 189, a quarter of the 720 MEPs. Their former "coalition" partners, the Socialists and Democrats (S&D), remained stable, losing only two seats, while the liberal Renew Europe lost 23 seats. This is not a severe loss in EP terms, as the three centrist groups still have a comfortable majority: 403 MEPs compared to the minimum of 361. Add to this figure the Greens, the other big loser of the European elections alongside Renew Europe; the four groups account for 63% of the EP – although they accounted for 69% in the last cycle. The EPP's victory boosted Ursula von der Leyen's chances of being re-elected as the President of the European Commission, despite Viktor Orbán's opposition.

There has been no breakthrough of the far right, but the gradual shift to the right continues in the European Parliament and the Member States, causing leadership challenges potentially even in the EU. As we predicted in our study last December, the far-right landslide did not happen, as things stand, the two radical (far) right groups, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the Identity and Democracy (ID), will together have 131 MEPs (ECR 73, ID 58), just 18% of the 720 MEPs. Including the 11 Fidesz MEPs, their share is almost 20%. In addition, 16 far-right parties will have a total of 45 MEPs (5.7%), who were non-aligned in the previous legislature or whose group affiliation is still unknown as newcomers. In total, the radical (far) right parties will, therefore, make up 25% of the European Parliament, which is below previous estimates and expectations (for instance, the Europe Elects' seat projection in April predicted 84 seats for the ECR). However, radical (far) right parties in several countries (e.g., France, Italy, the Netherlands, Germany, and Austria) have achieved a high position, although this was to be expected. This trend could continue in national elections later this year (Austria has a general election and Germany has three state elections in the autumn), which could weaken the mainstream forces in the Member States and cause difficulties for the leadership in the strongest EU countries (e.g., Germany), with implications for the EU. In this respect, France could be a test case, with a snap election announced for the end of June.

The fragmented far right continues to have limited institutional influence. The European far right was in turmoil in the weeks leading up to the European elections. The exclusion of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) from the ID group has highlighted not only the ideological differences among parties that appeared to be united but, above all, differences in political interests. It remains to be seen what swifts will unfold between the ECR and the ID groups and among the non-affiliated parties, whether the two separate groups will continue to exist, and whether a third group will emerge under the leadership of the AfD. These movements also depend on the development of EPP-ECR and EPP-S&D relations. Even if broader cooperation between the members of the ECR and the ID were to be established, it would certainly not cover the whole spectrum, so the far right would probably be more fragmented than integrated. However, in response to the challenge from the far right, the EPP is likely to continue its gradual shift to the right, with a partial adoption of radical positions. This may make it more difficult for the centrist coalition to function, increasing the importance of ad hoc cooperation. But without sufficient political weight, the influence of the far right will remain limited.

Authoritarians have a slightly better chance of influencing the European Parliament. In our study published in May, we showed that the members of the outgoing Parliament from the far-left (the Left) and the far-right (ID) groups were the most lenient and accommodating towards authoritarian countries such as Russia and China. As a result, these countries consider these radical MEPs as primary targets and instruments of influence – as confirmed by recent investigations into prominent members of the AfD and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). While these groups together accounted for 12.2% of the former 705-seat European Parliament (ID 49 seats, the Left 37 seats), they now account for 15.1 % (ID: 58 + 15 from the newly excluded AfD, the Left: 36). The change is due to the Polish Konfederacja, the Bulgarian Vazrazhdane and the Romanian AUR, as well as the strengthening of the AfD and the FPÖ. Simultaneously, the centrist parties (Renew Europe, Greens, EPP, and S&D), which are the bulwark against authoritarian influence, have weakened by a larger degree, from 69% to 62.6%, as shown above. The uncertainty is also heightened by the large number of newly elected MEPs (55; 7.6%), whose group affiliation is not yet known, and the 45 non-attached members (6.2%). A far-right political group led by the AfD could further increase the influence of authoritarian forces, to which Our Homeland could also contribute its small share.

Viktor Orbán seems to be swimming against the mainstream, even on the far right. While most far-right parties (e.g., Meloni, Le Pen, Wilders), except the most extreme ones, tend to gravitate towards the center and strike a more moderate tone to attract voters and other parties, Fidesz's primary focus is on outbursts and scandals, vocal protests, and vetoes, especially regarding support for Ukraine. If Fidesz is indeed seeking to join the ECR group, it will need to make significant concessions, particularly on its stance regarding Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Otherwise, the party will be left with ID, which for the time being, at least until the French snap elections, is further away from power and influence, or it will remain independent.

After stopping Brussels, Hungary will take charge. In his election night speech, Viktor Orbán announced that Fidesz’s victory had stopped Brussels, just three weeks before Hungary takes over the six-month rotating EU presidency on 1 July. There will be little time for productive work due to the institutional interregnum, with the setting up of the new European Parliament and the Commission, but there will be important decisions, such as the extension of sanctions against Russia, which are due to expire on 15 September. Although the government is, in principle, preparing for a smooth presidency, it will have to cut the ever-growing Gordian Knot of its own anti-EU and anti-Ukraine rhetoric aimed at domestic audiences, and abandon its only remaining means of influencing decisions and asserting interests: obstruction, and blocking. At the same time, the government will aim to capitalize on the symbolic power of the presidency to promote its ideas and messages and to exaggerate its international position.