Hungary and Slovakia could decouple from Russian energy

Disclaimer

The Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD) and the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA) prepared a report titled The Last Mile: Phasing Out Russian Oil and Gas in Central Europe. The report is part of their research monitoring Russian fossil energy imports, which have partly financed Russian aggression against Ukraine. Please find below a summary of this report in English.

The full English version is available here.

Political Capital is collaborating with the authors on the distribution of the study in Hungary

Key findings

- Hungary and Slovakia show no sign of decoupling from Russian crude despite the EU legal text stating this was the exemption’s purpose. Hungary increased its Russian crude reliance from 61% pre-invasion to 86% in 2024, Slovakia, although the trend was the opposite, had essentially reached the same level of dependence last year.

- Phasing out Russian oil is fully feasible for Hungary and Slovakia, as the Adria pipeline from Croatia supplying non-Russian crude can meet their combined needs.

- Despite the EU’s push to reduce dependency on Russian gas, Hungary and Slovakia have increased their reliance on the Russian supply. In 2024, Hungary and Slovakia’s reliance on Russian pipeline gas supply increased to 70%, up from 57% in 2021

- Europe can phase out Russian gas without risking supply security. The EU should set a legal deadline for phasing out all Russian pipeline gas imports by the end of 2025

- The EU should sanction Rosatom and all of its subsidiaries to fast-track the process of reactor fuel diversification. Several EU countries, including Hungary and Slovakia, remain heavily dependent on the Kremlin’s nuclear monopoly, Rosatom, through fuel exports.

Introduction

The EU granted Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic an exemption from the Russian crude oil ban as part of its sixth sanctions package adopted in 2022. This exemption allowed these landlocked countries to continue receiving Russian crude oil by pipeline, despite the general EU embargo on Russian seaborne oil that took effect in December 2022. The purpose of the EU derogation was to give these countries time to reduce their reliance on Russia. While the Czech Republic has phased out Russian oil, Hungary and Slovakia have shown no real intention of decoupling from Russian crude. Instead, they have used their exemptions to threaten to veto EU sanctions, linking their positions to continued Russian energy transit. The EU's oil derogation for Hungary and Slovakia has ultimately weakened a common EU position on Ukraine and sanctions unity against Russia.

While Hungary and Slovakia have offered weak justifications for continuing Russia's crude imports, there are no technical or economic reasons for maintaining the EU’s sanctions exemption for these Central European countries.

Meanwhile, the EU has pushed to reduce dependency on Russian gas. Despite this effort, Hungary and Slovakia have ramped up their imports via the TurkStream pipeline, increasing their reliance on the Russian pipeline gas supply. After the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the two countries have also stockpiled Russian nuclear fuel.

No sign of decoupling from Russian oil

Hungary and Slovakia depend on two crude pipelines: the Druzhba, which delivers Russian crude via Ukraine, and the Adria pipeline, operated by state-owned Croatian company JANAF, which supplies non-Russian crude from the Adriatic coast. Hungary receives non-Russian crude directly via Adria, whereas Slovakia accesses it through an interconnection where the Adria feeds into the southern part of the Druzhba pipeline.

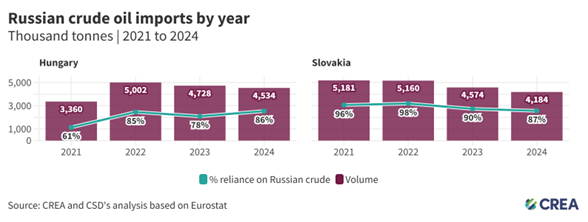

Figure 1: Hungary and Slovakia’s Russian crude oil imports by year

Hungary and Slovakia have shown no real signs of decoupling from Russian crude oil despite the EU legal text stating this was the purpose of the exemption.

Hungary increased its reliance on Russian crude oil from the pre-invasion 61% to 86% by 2024, while Slovakia remained heavily dependent, with only a modest reduction from 96% to 87%. By 2024, the two countries’ dependence on Russian crude was nearly identical.

The two countries’ imports of Russian crude oil since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine sent the Kremlin EUR 5.4 billion in tax revenues – the equivalent of the cost of purchasing 1,800 Iskander-M missiles that have been used to destroy Ukrainian infrastructure and kill Ukrainian citizens.

Over the last two decades, MOL – a Hungarian oil and gas company with substantial indirect state ownership through foundations – has emerged as one of the biggest oil companies in the region. Since 2010, the Hungarian government has politically supported the MOL’s expanding market share in Central and Southeastern Europe. MOL’s market success has also been closely tied to the regional expansion of Russia’s largest private oil company, Lukoil. While most European firms have moved to diversify away from Russian energy since the 2014 annexation of Crimea, MOL has instead doubled down on its cooperation with Lukoil, particularly in crude supply and downstream operations like retail gas stations. This strategic partnership has proven lucrative for Lukoil, allowing it to maintain an indirect market presence while avoiding Western sanctions.

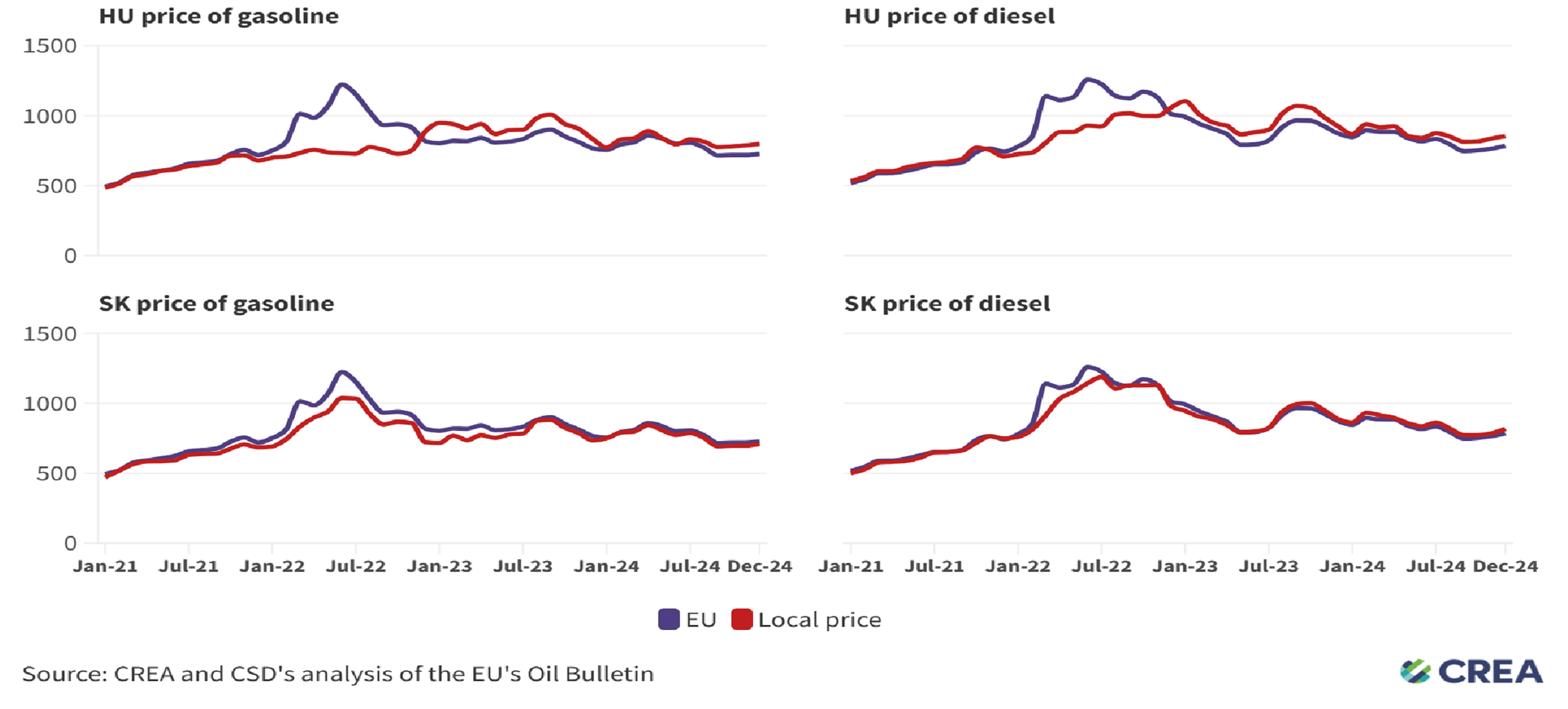

Figure 2: Pre-tax prices of gasoline and diesel in Hungary and Slovakia compared to the EU average

Discounted Russian crude oil has fueled both MOL's profits and the Hungarian state's revenues. In early 2023, Hungary’s fuel prices exceeded the EU’s average despite a 77% average discount on Russian crude compared to non-Russian crude imported via the Adria pipeline. MOL captured the full benefit of discounted Russian crude without passing savings on to consumers. The company’s operating income rose by 30% in comparison to pre-invasion levels, even though domestic pre-tax fuel prices in Hungary remained 5% above the EU average in 2024. The company's profits were partially curbed by the Hungarian government's decision to impose a steep windfall tax on petroleum companies' excess profits starting in June 2022. Between the start of 2022 and May 2024, the Hungarian government and MOL achieved a total of EUR 1.7 billion in “extra profit” from purchasing discounted Russian crude oil while maintaining higher consumer prices.

Phasing out Russian oil is possible

Although Hungary and Slovakia have consistently opposed an EU-wide ban on Russian oil, phasing out Russian crude is feasible for them because the Adria pipeline can supply them with non-Russian crude. Hungary claimed that JANAF had not undertaken the necessary capacity upgrades, but Croatia publicly rejected this claim, stating that the Adria pipeline could fully replace the Russian oil supply. In 2023, MOL participated in technical tests with JANAF that confirmed the pipeline can meet the consumption needs of Hungary and Slovakia.

Hungary’s other principal objection to sourcing its oil via the Adria pipeline is JANAF’s alleged high transit fees and Croatia’s supposed lack of reliability as an energy partner. While the exact fees remain undisclosed, both the Druzhba and Adria pipelines employ similar methodologies to calculate their charges based on transport volume and distance. Given that the Adria pipeline is shorter to the Hungarian border and safer than the Druzhba pipeline, which entails huge security supply risks as it flows through a war zone, importing oil from Croatia should be economically viable.

MOL has confirmed that its refineries in Hungary and Slovakia are technically capable of processing non-Russian crude, though with lower yield efficiency and higher unit cost. MOL’s own operational record during the Druzhba pipeline disruptions has demonstrated its adaptability to reduce reliance on Russian crude. In response to the Druzhba pipeline contamination in 2019, Hungary significantly increased non-Russian crude imports via the Adria pipeline, temporarily reducing its reliance on Russian oil to 48%.

The Russian Gas Fortress

More than three years after the Kremlin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the EU has reduced its pipeline natural gas imports from Russia from 40% in 2021 to 11% in 2024. This decline occurred partly because Russia cut off the gas supply to buyers who refused to pay in rubles. Additionally, the transit agreement between Ukraine and Russia expired at the end of 2024, which cut off most pipeline flows.

One notable exception to the EU’s reduced imports of Russian gas has been gas transported via the TurkStream pipeline. Since its launch in 2021, transit volumes of Russian gas to the EU have skyrocketed, generating EUR 22 billion in revenue for the Kremlin while supplying gas to Greece, the Western Balkans, Romania, Moldova, Hungary, and Slovakia. However, TurkStream undermines European energy diversification efforts by flooding the market with discounted gas. In 2024, the Russian pipeline gas was estimated to be sold to European buyers via TurkStream at prices 12-15% lower than alternative options. This discounted gas has left buyers vulnerable to energy blackmail, discouraged production in the Black Sea, and stifled liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports.

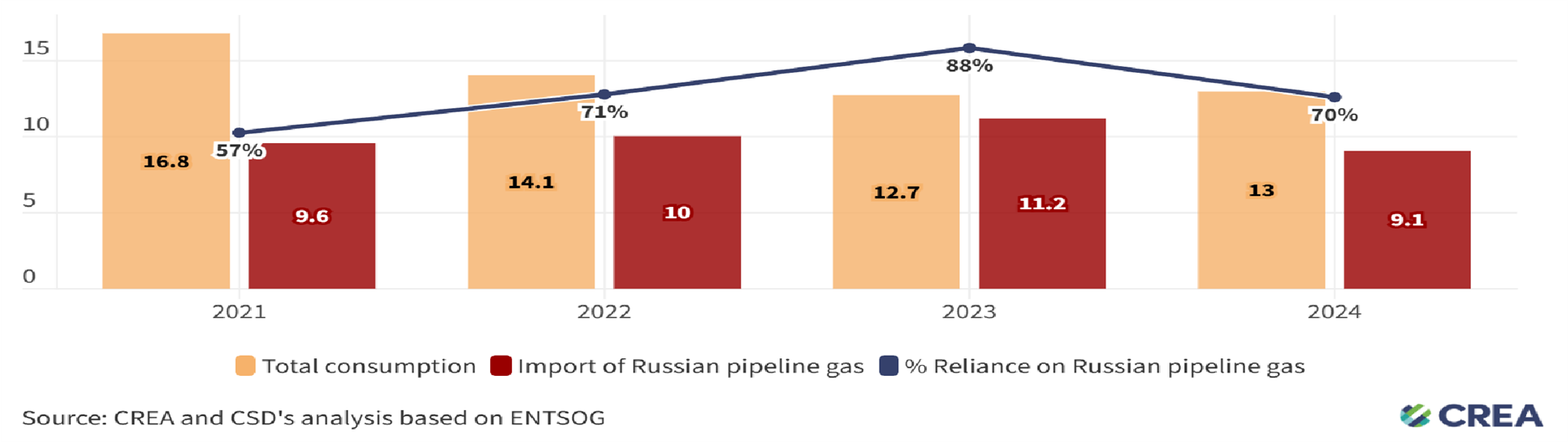

Figure 3: Hungary and Slovakia’s combined reliance on Russian pipeline natural gas

The main reason for the expansion of Russian gas flows through TurkStream is Hungary and Slovakia, which have become the biggest buyers of Russian gas. Hungary and Slovakia’s combined imports of Russian gas fell by only 5.5% in 2024, whilst the rest of the EU reduced imports by 81% compared to pre-invasion levels. During this time period, Hungary and Slovakia’s total gas consumption dropped 23%, therefore highlighting how the two countries’ reliance on Russia rose from 57% in 2021 to 70% in 2024.

Hungary, which used to be a major transit country for Russian gas until the supply through Ukraine ended, has transformed into a strategic Kremlin-backed gas hub for Central and Southeast Europe. Hence, Hungary has increased its re-exports of Russian gas to Slovakia as it is committed to maintaining its long-term gas contract with Gazprom.

Europe can manage without Russian gas

Europe should set a deadline for phasing out all Russian gas imports by the end of 2025, including prohibiting flows through TurkStream, as alternative gas supply routes and infrastructure now sufficiently mitigate potential security of supply risks. These alternative routes now have the capacity to bring in three and a half times more gas than current Russian supplies. This is possible because Greece, Bulgaria, Romania, Serbia, and Hungary have completed several strategic interconnectors and LNG regasification projects that allow for reverse flow gas deliveries at most border points and the delivery of non-Russian gas from the global market.

Hungary would need to deepen cooperation with regional partners to phase out Russian natural gas. Alternatives include LNG imports through Croatia’s Krk terminal, increased west-east flows from Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, and closer coordination with Austria to access Western European LNG and Norwegian gas.

The silent Russian nuclear dependence

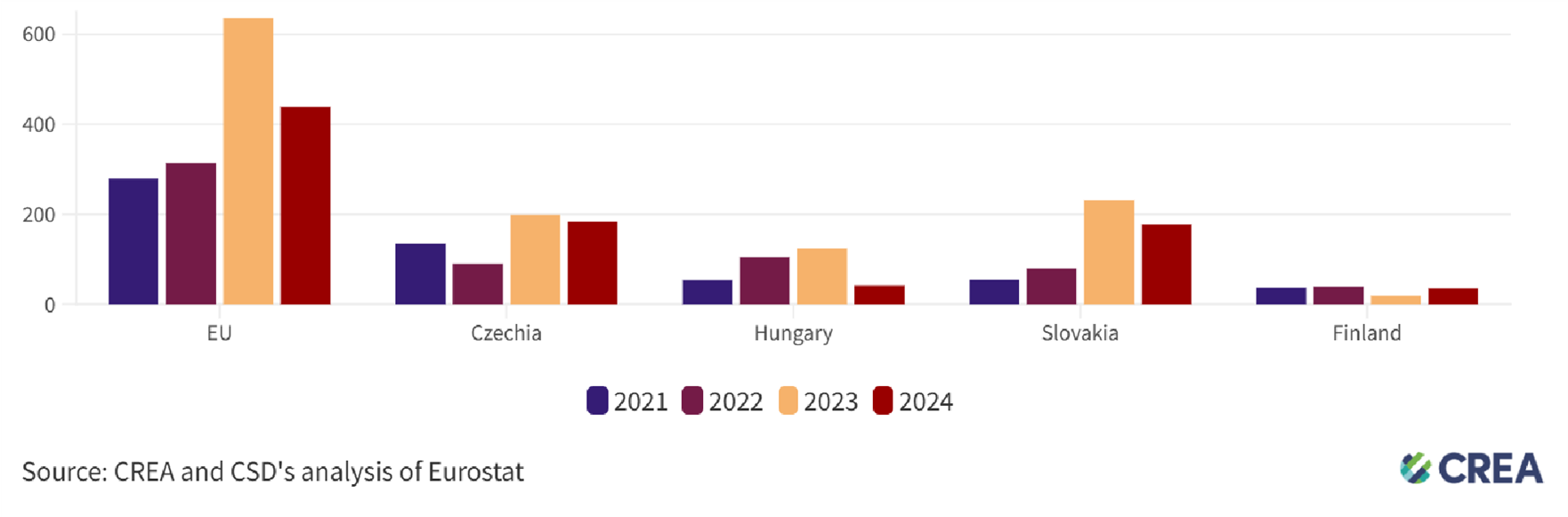

There are currently no sanctions against the Russian nuclear sector. However, European buyers began stockpiling in anticipation of potential disruptions and sanctions against the Russian nuclear industry. Hungary, where nuclear energy accounts for 44% of power generation, dramatically increased its nuclear fuel imports by 96% in 2022 – the largest rise among EU countries. Russian reactor fuel import continued to grow, increasing by another 19% in 2023. However, despite the sharp rise in previous years, Hungary’s nuclear fuel imports in 2024 dropped by 22% compared to 2021 levels. Hungary’s deal with Rosatom to expand the Paks II nuclear plant has also entrenched the country in long-term technological and financial dependence on Russia.

Figure 4: The EU’s annual imports of Russian nuclear fuel by country

Despite the jump in imports from Russia, Hungary has taken steps to diversify its nuclear fuel supply. Hungary’s MVM Paks NPP entered into a fuel supply contract with France’s Framatome to ensure the continued operation of the Paks plant, which provides approximately half of the country’s electricity. However, the French firm has signed agreements with the Russian Rosatom for the production of nuclear fuel for VVER reactors, including those in Hungary. Hungary could also strengthen its energy sovereignty by diversifying its use of Western technology that is already compatible with VVER reactors. A growing number of countries have turned to Westinghouse to secure a stable nuclear fuel supply.

Policy recommendations

To end Central Europe’s role as a backdoor for Russian fossil fuel revenues, the EU must close the sanctions loopholes and accelerate the complete phaseout of Russian oil and gas imports in Hungary and Slovakia.

- The EU should end the derogation from the EU ban on Russian oil imports under Regulation 833/2014, which has allowed Hungary and Slovakia to sustain a strategic dependence on Russian oil. The legal basis for the derogation requires Member States to take all necessary measures to replace Russian supply, which Hungary and Slovakia have failed to do.

- The European Commission should adopt a new roadmap for phasing out all Russian gas imports, including deliveries through TurkStream. This roadmap should focus on coordinated LNG imports and the use of reverse-flow interconnection capacities across Central and Southeast Europe.

- MOL should allow its long-term agreement with Lukoil for the delivery of crude oil via the Druzhba pipeline to expire at the end of June 2025. Any extension of the supply contract should be viewed as a Hungarian strategy to create long-term dependence on Russia in the region

- Hungary and Slovakia should maximize the utilization of the Adria pipeline from the Adriatic coast of Croatia. Technical tests show that the capacity of the pipeline exceeds the combined needs of the countries and will be able to replace Russian oil supplies fully.

- In cooperation with the EU, Hungary and Croatia should launch an independent audit of JANAF transit fees to dispel claims of non-competitiveness and introduce an arbitration framework to resolve payment disputes with JANAF. This would address the concerns of Hungarian buyers that JANAF is an unreliable and unverified supplier.

- The EU should sanction Rosatom and all of its subsidiaries as a policy instrument to fast-track the process of reactor fuel diversification.