Hidden Agendas: Fake Profiles on Facebook ahead of Hungary's Upcoming Elections

Hundreds of coordinated fake profiles, often with images from Russian social media, are engaged in pro-government influence operations on Facebook ahead of municipal and EP elections

In the last weeks, we identified over 500 fake profiles spreading pro-government propaganda on Facebook in Hungary. These profiles have infiltrated over 450 Facebook groups nationwide, potentially reaching tens of thousands of Hungarian users. Groups in the capital, Budapest and the metropolitan area are strongly affected, with Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony being the main target of the coordinated, systemic influence operation. The fake profiles mostly share articles from government-organized media outlets to amplify the government’s messages, and their profile and cover pictures are often obtained from Russian social media sites. While they can already reach a significant number of Hungarian Facebook users, the amount and activity of fake profiles will likely increase with the municipal and European Parliament elections approaching. Hence, the coordinated influence operation can significantly affect the integrity of the two elections to be held simultaneously in June 2024. The analysis below presents the main findings of our ongoing investigation and delivers evidence proving what we have found is a coordinated and systemic influence operation. In addition to the name and country, changing gender is not a barrier for trolls.

In Hungary, because of the parliament’s decision, the municipal elections in 2024 will be held on the same day as the EP elections – in order that the government makes the life of the opposition more difficult and to keep control of the agenda. The campaign has already started with high intensity, with the government, Fidesz and the government-organized media mainly blaming the opposition for incompetence. The influence operation we uncovered fits into this campaign line.

The administrator of a Facebook group for Budapest district issues, run by civil society activists, drew our attention to suspicious profiles that posted articles which were utterly different from the group's topic in question, typically attacking the local government of Budapest in a campaign-like manner – in common terms, a typical troll’s behavior. That’s how our investigation started. Since Political Capital has been researching this phenomenon (in official terms: "inauthentic online behavior") in Hungary for years, within a few weeks, we could identify over 500 fake profiles created gradually in distinct waves since the beginning of 2022. Their activity mainly aims to infiltrate political messages echoing the government’s narratives into community groups (both political and non-political ones, like give-and-take forums) and to spread disinformation and defamatory content discrediting opposition parties and politicians, especially Budapest Mayor Gergely Karácsony. The strategy is based on the principle of how social media works: only a few fake profiles are enough to trigger a comment war by sharing an article, which makes the piece trending in the respective group.

The coordinated influence operation exposed by Political Capital reinforces the hegemony of the government’s narrative over the information space in Hungary and extends its dominance on Facebook, the central social media platform in Hungary. Over the years, the government has gained control over the vast majority of public affairs media. Furthermore, its political, outdoor advertisement spending (including the campaigns outsourced to government-organized organizations, so-called GONGOs) exceeds by far the spending of opposition parties and their affiliated entities. Moreover, the government has also established its dominance on Facebook in recent years with the help of ads worth HUF billions, a massive army of government influencers and dubious pages. In addition to all that, the government’s messages are now being disseminated even by fake profiles in a coordinated influence operation. Here's how.

How do we know that these are fake profiles?

The following characteristics helped us identify these fake profiles and prove their inauthenticity:

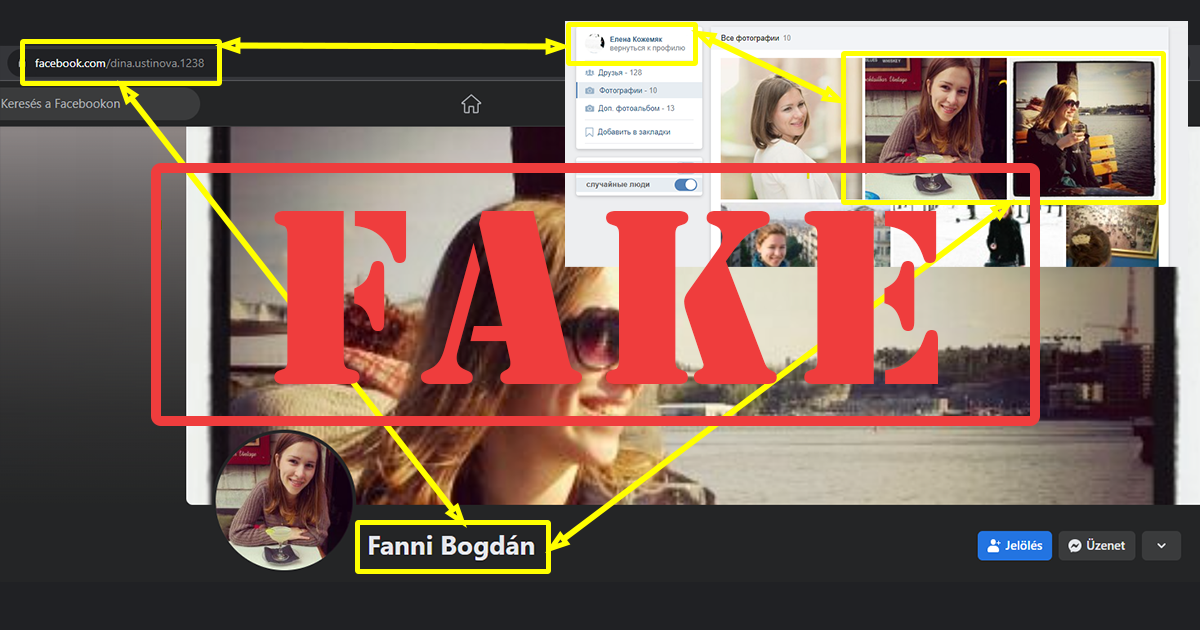

- Their profile and cover images stem from existing foreign individuals’ public social media pages, mainly from Russian VKontakte and, in some cases, other sites (such as dating sites, etc.). However, this does not necessarily imply that the fake profiles are of Russian origin. Pictures may have been taken from Vkontakte simply because they are harder to detect, as most reverse image search engines do not find them.

- Although the profiles have Hungarian names, their URLs often contain foreign names, potentially revealing their origin. The screenshot below shows an example of a profile initially belonging to Iulechka Elfimova, now called Ábel Novák. So, in addition to the name and country, changing gender is not a barrier for trolls.

- The profiles do not disclose any information beyond what is mandatory. Hence, only the profile picture, the cover picture, the date they were set up (which cannot be hidden) and sometimes their location is displayed on their wall. Moreover, they do not publicly post anything on their wall except for completely impersonal and mixed re-shared content.

How do we know that this is a coordinated operation?

The fake profiles’ activity follows the same pattern, which suggests central coordination.

- After publishing the first results of our investigation in Hungarian language on 20 September, the foreign names in the URLs were, in many cases, changed in one single day to match the respective profiles’ Hungarian names.

- After their activation, the fake profiles joined public Facebook groups nationwide to influence members’ political views. The groups they have joined include non-political local community groups and groups with public affairs content with pro-government, anti-government and even pro-opposition leaning. The fake profiles are often members of multiple groups. In many cases, their activity pattern suggests strategic deployment: they share various types of content in different kinds of groups.

- The fake profiles publish posts with various intensities in the respective groups they joined. The reason for this may be caution: they do not want to arouse the suspicion of either the group’s moderator or Facebook's monitoring system by frequently sharing articles that deviate from the group’s topic. There are also ‘sleeping’ profiles that are members of a group but have not shared any content yet.

Where do these fake profiles come from, and who is behind them?

Our investigation cannot reveal the origin of the fake profiles; only Meta, the data owner, could shed light on this. However, there are two options.

- The profiles may have been created as fake initially.

- Yet, it is also possible that “authentic” individuals initially created these profiles organically for their private personal use, which were later hacked and stolen. The current coordinators of the profiles could have either bought them on the dark web (according to an article on Privacy Affairs, a hacked Facebook account costs around $25 these days) or obtained them from organizations that no longer needed them. Then, they changed their names and set up new profile and cover images that were hard to be traced back.

We can also not identify the individuals behind the fake profiles and their location by ourselves. Nevertheless, a Hungarian group is likely in control of these fake profiles. Although the number of profiles is extensive, their individual activity is still low, so controlling them might not be too labor-intensive yet, requiring the active involvement of just a few people.

What is the aim of this coordinated influence operation?

While we cannot identify who coordinates the influence operation and manages the fake profiles, based on the content shared, we can conclude what the intention of the coordinators can be and who can benefit from their activities. The coordinated influence operation clearly serves political goals aiming to amplify government propaganda.

- The fake profiles share highly biased, polarizing, propaganda-like content from government-organized media, often containing disinformation.

- In non-political groups dealing with local issues, they mainly share content that is highly critical of opposition parties and politicians and which often uses defamatory language to discredit and stigmatize them. At the same time, the content shared portrays the role of the government and government politicians very positively.

- While the fake profiles are present in many local groups throughout the country, their activity is particularly strong in groups related to the capital Budapest and its metropolitan area. In these groups, they mostly share articles sharply critical of the Budapest city administration and of Mayor Gergely Karácsony personally. The aim is to discredit the capital's administration and especially the mayor – for example, concerning the issue of traffic jams, which happens to be the main topic on Fidesz's agenda and in the government-organized media concerning the capital.

What is the scale of this coordinated influence operation?

By Hungarian standards, these fake profiles reach a significant number of Facebook users and potential voters. The thorough investigation of over 170 fake profiles that were created in the summer of 2023 revealed that these joined over 320 Facebook groups, including around 200 focusing on local issues relating to 84 localities across the country. As mentioned earlier, the capital Budapest, which is the main opposition stronghold in the country, and its congested urban area are significantly affected.

As we approach the municipal and European Parliament elections that will take place in June 2024, the number of fake profiles and their activity are likely to increase. The current low-intensity period is presumably only a test phase, and it is logical to assume that non-Budapest local community groups will also see an increasing number of fake profiles changing name or even gender.

Methodology: How have we uncovered the network of fake profiles?

As a starting point, we identified the most shared articles and then looked for which public groups they were shared in. For both steps, we used CrowdTangle, Meta’s public insights tool. To examine the profiles of those who shared articles, we used public data available through Facebook's search engine. The origin of the profile and cover images was traced using Yandex's reverse image search. Newer groups, fake profiles and articles were identified using a snowball method, and during iterations, we kept finding new fake profiles and local groups they had joined. Thus, it is likely that the fake profiles we have identified so far cover only a fraction of the total phenomenon. That is why we continue our investigation.