Fidesz’s EP election dreams did not come true

Fidesz failed to gain two-thirds of the seats allocated to Hungary and its European position became unstable. The ruling party made a lot of enemies in the EPP, while its influence would diminish considerably if it sat in Salvini’s EAPN. Fidesz sacrificed its positions in the European Parliament on the altar of domestic politics with an anti-EPP campaign. Fidesz’s large (but not record large) victory is accompanied by it losing influence on the European level.

The consequences of the EP elections on the European level

- Higher voter turnout, more legitimacy. The Europe-wide voter turnout was over 50% for the first time since 1994 (50.95% according to preliminary data from Monday morning), which increases the EP’s legitimacy. This is partly the result of the fact that European topics became prevalent in the campaign, such as migration and environmental protection.

- The mainstream remains strong; a more fragmented but not Eurosceptic Parliament is in the making. The European People’s Party (EPP) and the Socialists and Democrats (S&D) lost their joint majority in the European Parliament for the first time since the institution is elected by popular vote. Although Eurosceptic parties improved their overall result from five years ago, largely thanks to Salvini’s League and Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, green and liberal parties also profited from the losses of traditional centre-left and centre-right parties. The EPP remains the EP’s strongest group with 182 seats, its majority would not be in danger even if it lost Fidesz (13) and its ally (the Slovenian SDS [3]): the second-placed S&D currently has 147 seats. ALDE is firmly established as the third force in the European Parliament, while the Greens came close to matching the Salvini-led European Alliance of Peoples and Nations (EAPN) in size. The ECR will not only be weakened by losing the British Tories, but also by the appeal of EAPN. Nevertheless, the former has a chance to survive because the ECR’s anti-Russian parties (e.g., the Polish PiS) are unlikely to want to sit in the EAPN, a group filled with pro-Putin forces. Eurosceptic parties will have a very moderate effect on decision-making in the EP because the allocation of seats between pro-EU and anti-EU forces is about 67% for the former and 33% for the latter; while the cohesion of Eurosceptic groups is traditionally lower than that of mainstream party families.

- The election of the president of the European Commission (EC) will be a prolonged process. The president has to be nominated by the European Council (EuC) by qualified majority voting. The EU’s heads of states and heads of governments will meet the next time on 28 May for an informal dinner and the next EuC summit will take place on 20-21 June. Considering the fact that the nominee for the Commission presidency has to be approved by the absolute majority of MEPs, the representatives of the EP and the EuC will be holding regular discussions behind closed doors throughout the process. Manfred Weber, the lead candidate of the EPP and Angela Merkel’s pick to become president, still stands a chance to win the position, but the EuC had said before the election that they would not be bound by the Spitzenkandidat process. Weber’s chances are dampened by the fact that he does not enjoy French President Emmanuel Macron’s support (and, albeit it is less important in terms of his nomination, that of PM Viktor Orbán either).[1] EPP-affiliated Brexit chief negotiator Michel Barnier has the largest chance to become EC president besides Weber, both Macron and Orbán would react positively to his candidacy. If it was not the EPP’s lead candidate who became EC president, it could temporarily diminish the EP’s prestige and subsequently strengthen voices demanding the democratisation of the EU, especially from pro-EU forces; and the issue of transnational EP election lists could resurface.

- Eurosceptic and liberal parties both gained ground in V4 countries. More or less Eurosceptic parties won the elections in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland – and by a larger than expected margin in the latter case. However, liberal forces also performed well in multiple countries: the liberal PS-S (ALDE-EPP) won in Slovakia, while the Hungarian Momentum almost tripled its vote share since April 2018.

- The gains made by pro-Putin far-right and far-left parties will amplify the Kremlin’s voice in the European Parliament. These groups will continue voting along Russian interests in the EP, representing the sort of anti-sanctions and anti-Ukraine politics the Kremlin likes. At the same time, the gains of parties favouring deeper integration foreshadow that the voices of those demanding a stronger European security and defence policy could also become more prevalent. Thanks to far-right and pro-Kremlin forces, Russian disinformation (generally disseminated for domestic political purposes) has become a permanent part of European politics. Such manipulative narratives both help Moscow’s political allies through the Kremlin’s propaganda channels (Sputnik, RT) and attack the weak, liberal elite and the European project using migration and scaremongering about the loss of national identity and sovereignty. The purpose of information operations is promoting the Kremlin’s own geopolitical vision, the “Europe of nations,” which would dilute the European Union from the inside. The weakening of European integration and a stronger role for nation states would strengthen Moscow’s lobbying power in EU decision-making procedures, but the Union is currently unlikely to turn towards this direction. Disinformation will be an increasingly acute problem in the future, which renders it important that mainstream forces on the European and national levels take concrete steps to counter and control this phenomenon.

The consequences of the EP election in Hungary

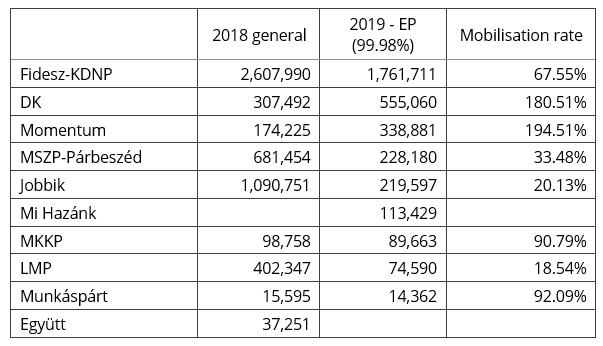

- Around 62% of Hungarian voters who cast a ballot within the country’s borders in last year’s general election took part in the 2019 EP election. Thus, in general, all parties would have had to mobilise this proportion of their voters from 2018 if they wanted to maintain their vote shares from the general election. Fidesz overperformed only slightly, MKKP fared much better, while DK and Momentum achieved a breakthrough by almost doubling the number of their voters. MSZP-Párbeszéd, Jobbik and LMP could only convince around one-fifth to one-third of their voters from 2018 to cast a ballot on them in 2019.

- The domestic results of the EP election in Hungary foreshadow the further amplification of identity politics and the polarisation of society. This is not only indicated by the 50-50 vote distribution between the ruling party and the opposition, but also by the fact that DK, one of the large winners among the opposition, is the party that is characterised the most by tribalism besides Fidesz.

- The largest surprise was the reshuffle of opposition parties that was not predicted by polling organisations. This could lead to the largest changes in the Hungarian political party system since 2010. The two large winners are DK and Momentum, the former could easily woo away the remaining voters of the MSZP. Jobbik, which is the primary target of Fidesz, is in survival mode at best, while LMP essentially disappeared. Mi Hazánk, which is strongly supported by government-controlled media, played its role in weakening Jobbik, but since there is barely any space left on the far right of the political spectrum because of FIdesz, its room for manoeuvre is not big.

- MSZP-Párbeszéd, campaigning with the fact that it is the only joint list in Hungary, failed, while parties with a separate identity that are beyond any suspicion of collaboration with the ruling party have gained ground. The results of opposition parties give a clear picture of the strength of their organisational network, which could be an essential deciding factor in the autumn municipal election. The nomination procedure of the opposition’s candidate for mayor of Budapest might be restarted and mayoral candidates in the districts of Budapest could be re-evaluated as well. However, it is unlikely that masses of new mayoral and local council candidates will emerge in the countryside.

- Although it did not achieve a two-thirds majority with 13 EP seats, Fidesz’s advantage over its domestic opposition remains massive. The basis of this is the efficient mobilisation machine of the ruling party built on its increasing financial and organisational resource advantage guaranteed by the increasingly authoritarian political system. At the same time, Fidesz’s 52.3% result has to be assessed in the context of almost inconceivable campaign spending, the party’s media dominance (mainly) in the countryside, the illegal unofficial voter registry lists openly waved around by Fidesz and the pressure the ruling party puts on the most vulnerable voters. Taking all this into account, the ruling party is not as strong as it shows itself to be.

- It is important with regards to the autumn municipal elections that Fidesz’s vote share fell from 43.75% to 41.2% in Budapest, and it only performed better than 50% in 7 out of the 23 cities with county rights. Fidesz will draw the conclusion from this result that it has to step up against the opposition even stronger and it has to improve their organisational efforts until the municipal election. If opposition parties reopen public negotiations instead of focusing on local campaigns and organisational work, they will be beaten in the municipal elections.

This analysis is available as a pdf document here.

[1] If the EC president was nominated without Emmanuel Macron’s support, it would constitute a massive domestic political and foreign policy defeat for the French president, who is personally against the Spitzenkandidat system. Although Macron never said he did not support Weber, he did say that a candidate for the EU job should have “experience at the highest governmental level or European Commission level” – which disqualifies the Bavarian candidate.